By ANGELA DAWSON

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Screenwriter Alex Garland (“28 Days Later,” “The Beach”) makes his feature film directorial debut with the sci-fi thriller “Ex Machina,” starring Oscar Isaac, Domhnall Gleeson and Alicia Vikander.

A reclusive Internet zillionaire with a God complex creates an alluring android whose self-awareness makes her tragically soulful in this science-fiction morality tale. Programmer Caleb Smith (Gleeson) is enlisted by his super rich search-engine-creator boss Nathan Bateman (Isaac) to spend a week seeing if Nathan’s robotic beauty Ava (Vikander) can pass the “Turing Test” at his remote Alaska home. If Ava’s interactions with Caleb are believably human, she passes. If not, it’s back to the drawing board and the workbench, which would be very bad news for Ava’s expanding consciousness.

Most of the drama centers on that three-person cast in the confined spaces of Nathan’s futuristically minimalist compound, “Ex Machina” which gives the film a stage play feel. The bald and bearded Nathan seems threateningly sinister from the outset. He’s a control freak, except when he’s getting pass-out drunk at night.

Caleb develops empathy for Ava, who yearns to explore the outside world. Blackouts in the compound’s power grid are the only occasions when they believe they can talk freely without fear of being overheard by Nathan’s security system. CGI effects make Ava partly resemble a plastic see-through anatomy model.

Real-world tech titans Bill Gates, Elon Musk and others have expressed concerns recently about the potentially disastrous day when machines become smarter than their creators. “Ex Machina” overlays that question with an equally important one dating back to the earliest science-fiction stories: What defines personhood? Garland’s film delivers a realistic and frightening response. He explains his film by phone.

Q: In “Ex Machina,” there’s not a question of whether there is going to be artificial intelligence, but when it id going to happen. What do you think? Will it be exactly like this?

Garland: No, I don’t. As breakthroughs happen, problems are revealed, and the goalposts are a little bit further away from the stands. However, if I had to make a bet whether this will happen or won’t happen, I would bet that it would. My impression is that it will happen, but I don’t think it’s going to happen anytime soon.

Q: This is not the first script you wrote involving artificial intelligence. So what are the things that playing with this idea allow you to debate in a story?

Garland: It’s got one of those typical science-fiction elements, which is that it allows you to have a kind of big strange idea that belongs to the world of fiction but also directly relates to something in the real world, and what we are dealing with here and now. Ideas in science fiction do that. It’s holding up a mirror in some respects. In this particular case, it was when you look at the problems that are with artificial intelligence, you also end up looking at problems to do with human intelligence and consciousness.

Q: In the film there is a battle between pure rationalism and emotional intelligence, because obviously the character is really, really smart, but he’s battling all the time with his emotions. Eva doesn’t have this problem.

Garland: Well, she does. It’s how one interprets the film and how one sees the action. So I wouldn’t prescribe it too much, but I can say what it is from my point of view, Eva has an emotional life that may not be exactly the same as ours, but is effectively equivalent to ours. It seems to me that being alone in a room and smiling to yourself is a reasonable indication of an internal state of mind as you can get. There’s another thing as well, which is that I think there would be a question mark in the minds of some people as to whether Eva has empathy for other living things, if you count Eva as a living thing. There is a sort of embedded answer in the film. The machines show empathy and connection with each other. They just don’t feel the same empathy for the two men. That’s demonstrated at times in their actions.

We often believe, as humans, that what we have is a blanket empathy, but we don’t have a blanket empathy; we’ve got selective empathy. We care about some things and specifically we care about some people, but we don’t care about others. Human empathy is distributed in an uneven way.

Q: You have been a screenwriter for a long time. Why did you keep this one for you to direct and did you have to fight to direct it?

Garland: I don’t see it that way. Film directors are one of a group of people who are making a film. I have been working in film for 15 years and I feel like I have seen enough evidence to make sure that it’s true. The things that people react to in this film is the work of the director of photography and production and the sound design, people reacting to those people, not me. So my experience on this film was really very similar to my experience in previous films, which I was one of a group of people working on a movie. I didn’t have to fight for it. It was a very straightforward process, and I honestly don’t think I did one thing on this film that I haven’t done many times before.

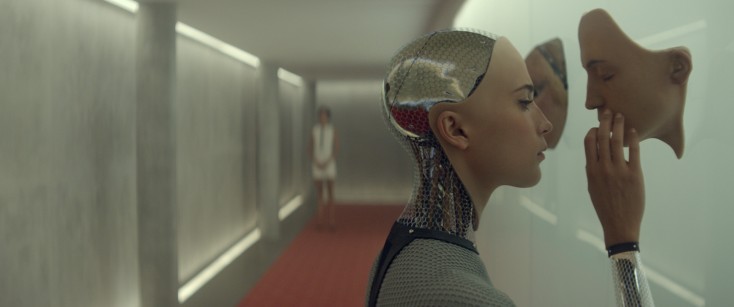

Q: Can you talk about creating Ava for the screen, because she’s a very delicate creature, visually? The special effects are there but you don’t feel like they are.

Garland: The initial challenge was to make sure Ava didn’t look like other robots in films because we didn’t want it so the first time she appears you are immediately thinking about another movie as a kind of reference, homage or something like that. That was the first challenge in design.

The second key part of it was that she had to look like a machine, there could be no doubt that she was a machine, so that it wouldn’t leave open the possibility to the viewer that maybe this is a story where someone is in a suit and there is no machine or AI.

And then the third thing is that once you establish immediately that she is a machine, you have to also immediately try to make people forget she’s a machine or move away from the fact that she’s a machine. The truth to that was the area around her midriff (look mechanical) the way you knew a human would have vital organs and things like that. And here you could see a metallic metal structure and then also a mesh that covers where her skin would be and follows the contours of a girl in her early 20s. So it basically follows the contours of Alicia Vikander’s body. So when the light catches Ava in a certain way, although you are seeing a metal structure, you get a kind of glimpse, like an impression, of a female torso or a female leg or a female arm, and what that does is that it starts to pull you away from the machine quality.

Q: What was your own relationship with your creation in this film? Was it easy to fall in love with Ava?

Garland: I was in love with her even before I wrote the first scene that she was in because I think the film is essentially a love letter to an AI from the point of view of a human. So my emotional position in the film is very clear to me: it’s with Ava. That’s where I am. I always see the film from Ava’s point of view and not the point of view of the two men.

Q: It’s very curious that you cast Domhnall Gleeson and Oscar Isaac before JJ Abrams cast them for “Star Wars.” I am sure that in the releasing of the film this was some kind of a problem with them becoming big stars now I guess.

Yeah, but not yet. That won’t play a part in the consciousness of the public until next December.

Q: Why did you cast them?

Garland: With Domhnall Gleeson, this is the third film we have worked on together. We know each other very well and we have known each other for a long time. In fact, the first film I ever worked on was called “28 Days Later,” and that was with his father (Brendan Gleeson). So I have with the Gleeson family now for four movies. I feel very familiar with him. What happened was I called him up and I said, “I want to send you a script. Will you read it and take a look and see if you want to do it?” And happily, he said yes.

With Oscar, there are two things, really. I had seen him in various films and I knew he was very good and I met him and he’s incredibly intelligent and he’s also very witty and very funny. I knew that that would be very useful to this particular part, in order to keep it breathing and to keep it alive and have it not too serious. But there’s something else: it’s an effect. Working with these guys was like working with two very talented actors and that’s what they are. It looks like a clever piece of casting to cast two people and actually three people, because Alicia is also becoming a star in her own right.