By ANGELA DAWSON

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Ema Ryan Yamazaki grew up in Japan reading H.A. and Margret Rey’s “Curious George” books in her native language. As a child, she assumed the good little monkey who was always very curious was Japanese. Only later did she learn what a global phenomenon the children’s books were, how many dedicated fans of all ages and nationalities they had and that the stories were not originally Japanese.

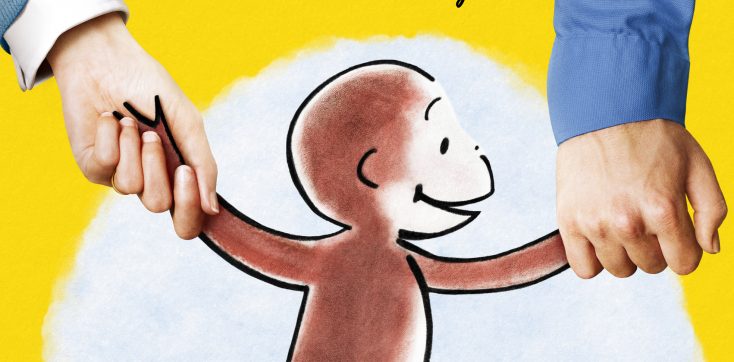

Drawn to filmmaking—she graduated in 2012 from the prestigious New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts—Yamazaki worked on a number of projects including a short documentary for Japan’s NHK public broadcasting on Martin Scorsese’s making of his feature film “Silence.” Most of her professional work has been as an editor, though. For her feature directorial debut, she reached back to her childhood to uncover the incredible story behind the story of Curious George and discovered the husband-and-wife creators of one of her favorite fictional characters. The result is the beautifully told and colorfully animated documentary “Monkey Business: The Adventures of Curious George’s Creators.” The documentary is available on demand and digital formats.

“I don’t think we ever get to ask ourselves who writes these amazing children’s books,” Yamazaki said of embarking on her first feature by phone. “Once I inquired and learned about (the Reys’) story, I was amazed no one had ever made a film about them before. I then embarked on this journey to discover who they were.”

The documentary recounts the remarkable lives of the Reys, German-Jews who narrowly escaped capture and probably death at the hands of the Nazis during World War II. The middle-aged couple fled France by bicycle just as German soldiers were marching into Paris. After escaping to neutral Portugal, the Reys sailed to Brazil before relocating to the U.S., where they pitched and sold their idea for a children’s book centered on the curious little monkey to publishing house Houghton Mifflin. The first book, simply titled “Curious George,” was published in 1941. (Initially named Fifi, the cute little simian’s name was changed to George, possibly after Founding Father George Washington, but no one alive knows for certain.)

Found in the jungle by a gentle human explorer, known as The Man in the Yellow Hat, George had many adventures in the human world to which he was unaccustomed, echoing in some ways the Reys’ own experience as immigrants in a foreign land. The Reys would eventually publish seven books detailing George and the Man in the Yellow Hat’s adventures, with George’s curiosity frequently getting him into trouble and the man and others helping him to get out of it. Their last book, “Curious George Goes to the Hospital,” was published in 1966.

Though referred to as a monkey, George is actually an ape because he has no tail. That didn’t concern the Reys, who were more interested in telling entertaining stories about their furry little hero that children and their parents could enjoy reading together than minute details. Hans, a preternaturally gifted artist, provided the bold colorful illustrations while Margret, a former advertising executive, wrote the words. Yamazaki enlisted fellow Tisch grad Jacob Kafka, an innovative young animator, to come up with the animation that seamlessly uses the Reys’ illustrations as well as chapters of their real-life story and turns them into animation in the film. (Some 15,000 “hand drawn” images were created via Kafka’s RoughAnimator software.)

Yamazaki was fortunate enough to meet through an acquaintance Lay Lee Ong, the literary executor of the Rey estate (Hans died in 1977; Margret died in 1996), who pointed the filmmaker to various sources for material for her film, including Louise Borden, who wrote “The Journey That Saved Curious George: The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey,” a book about the children’s book authors.

“She was very supportive from the beginning,” Yamazaki said of Ong. “Thanks to her and other people, historians who had done research on the Reys’ life, it helped inform me of the historical aspect. What I got to do was talk to dozens of people who knew them. (Borden’s) book was the only thing out there when I started the project so I learned about it shortly after I got interested (in making the documentary).”

Yamazaki also delved into the massive archive of Rey memorabilia at the University of Southern Mississippi, where approximately 300 boxes of original drawings, journals and letters the Reys wrote each other are stored.

“Gradually I put the film together, piece by piece. I just got obsessed with them,” she said.

Having worked with the Reys, Ong is a producer and also one of the many subjects interviewed in the film. Reys’ former neighbors (children at the time, now grown), relatives and colleagues also are interviewed about their interactions with the couple. Yamazaki also incorporates audio and video recordings of the Reys into the film. Emmy winner Sam Waterston (“Lost Civilizations,” “Law & Order”) provides the narration.

Making a film is never easy, but filming a first-time feature documentary poses a unique set of challenges, particularly with regard to financing. Yamazaki was determined to maintain creative control of her film so instead of going to a few deep-pocketed investors for capital, she used her own money (from her earnings as an editor) as well as crowdfunding. She raised $186,000 through a month-long Kickstarter effort last year, which she describes as the most challenging part of the filmmaking process.

“It was a lot of money to try and raise in 30 days,” the filmmaker recalls. “A lot of it came from people I didn’t know. Twenty-five days into the campaign, we still needed almost $100,000 but it really picked up at the end. A lot of support came from the Jewish community. Ultimately, we not only met our goal but a lot of distribution options came about from that campaign. The Orchard (film distributors) eventually bought the film. They got on board before the film was even finished. When they learned about the project, they gave us the rest of the funds to complete the film.”

“Monkey Business: The Adventures of Curious George’s Creators” had distribution locked in even before it was complete, which is a rare occurrence for an independent film let alone for a first-time filmmaker.

Yamazaki recalled that when she first heard the Reys on tape, she was “taken aback” by their German accents, but she quickly discerned their symbiotic relationship.

“They riffed off of each other as a tightly knit couple,” she said. “The more I discovered about them, I could tell who they were and their characteristics. Their life experiences show why we have Curious George. They’re reflected in George’s personality. I already was a George fan when I started this but I also became a Hans and Margret fan.”

Asked why she thinks Curious George remains so popular more than 75 years after it was first published, Yamazaki responded in her own accented voice, “It transcends cultures.”

Indeed, the “Curious George” books have been translated into more than 25 languages and have inspired films, TV shows and video games. Houghton Mifflin has owned the rights to Curious George, since Margret Rey’s death, and has published dozens of new adventures written and illustrated by other writers and artists.

“George does things that every kid wants to do,” Yamazaki said. “Even good kids live vicariously through him. He captures the most human parts of everyone—curiosity and being a little mischievous and an interest in adventure. As kids, we live within certain confines, and Curious George is free. The Man in the Yellow Hat is always there along with other people to take care of him. Even if he messes up, no one gets hurt, no one dies. It’s OK.”

Yamazaki said she’s been told that The Man the Yellow Hat is the perfect, ideal parent because he’s so patient. “No matter what, he forgives George and takes care of him and gets him out of trouble,” she noted. “That relationship also transcends generations.”