By JUDY SLOANE

Special to Front Row Features

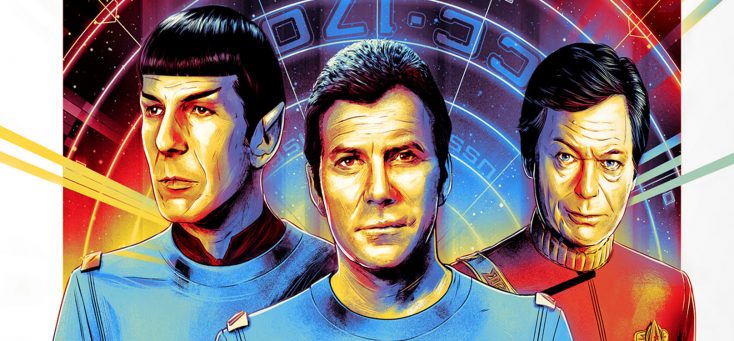

HOLLYWOOD—On Sept. 8, 1966, an extraordinary event occurred in television history, although it was missed by the majority of the viewing public. At 8 p.m. that night, “Star Trek” premiered on NBC. It chronicled the adventures of the Starship Enterprise and its crew, including Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner,) half-Vulcan/half-human science officer Spock (Leonard Nimoy) and the ship’s doctor, Leonard McCoy (DeForest Kelley). In 1969, after only three years and 79 episodes, the series, created by Gene Roddenberry, was cancelled because of dwindling ratings—hardly the stuff of TV classics.

In syndication, though, “Star Trek” took off at warp-speed to greater notoriety, spawning several new series and six movies with the original cast. The first film, which premiered in 1979, was “Star Trek: The Motion Picture,” directed by Robert Wise, who famously had directed “The Sound of Music”.

I spoke with Shatner, Nimoy and Kelley—the latter two have since passed—more than 20 years ago for “Film Review” magazine about their memories of the first film.

Judy Sloane: How did the movie come about?

William Shatner: “Star Wars” made everyone stand up. I’m sure that various executives realized that “Star Wars” was this big hit and they had this series, “Star Trek” that had caught everyone’s imagination, and they hadn’t come out with a big motion picture.

Sloane: It had been 10 years since you played the role. Was it easy to slip back into the character of Captain Kirk?

Shatner: I’d forgotten what I had done and how I’d played it, so I had to look at some of the segments of television. I had to recollect standing up straight and looking proud and being a military man.

Sloane: Leonard, I read your agent was scared to call you about “Star Trek: The Motion Picture.” Is that correct?

Leonard Nimoy: Partially valid, but out of context. At that particular time, I had a lawsuit pending against Paramount, so although it might seem as though it was a disinterest in “Star Trek,” that wasn’t the case.

Sloane: Once you became involved with the movie, were you consulted in any way about ideas for the character?

Nimoy: When the lawsuit was settled, I then read the existing script for the first motion picture. There was no Spock in it, so from that point on it was all about consultation.

Sloane: DeForest, what was it like to be reunited with the cast?

DeForest Kelley: We were all just looking around and looking at each other with many memories going through our minds. It was almost like a bunch of ghosts who have all passed away and they brought us back together again.

Nimoy: There was, of course, this enormous sense of re-gathering of family but, at the same time, what was dominate was the alienation of the Spock character. You see Spock arrive in this very dramatic condition, where he hardly takes notice of the people around him and sets to work in dealing with what’s wrong with the ship. It was very difficult because the character was so into a state of separation, and that’s what I was playing and preoccupied with.

Sloane: DeForest, you had such a great rapport with Leonard in the series, so nine years later, when you did the first motion picture, was that rapport instantly there?

Kelley: It fell right into place. Just so natural. It was as if we had done it yesterday. You’re right, the fortunate thing about that series was the chemistry of the people, and it was either a magical bit of casting or a great bit of luck.

Sloane: The ship’s bridge (in the movie) was so different from the original (TV series set). Did that squash any nostalgic feelings you might have had when you walked on the set?

Shatner: Everything was so big. It felt strange that something that was way in the past had been recreated.

Nimoy: There was a sense that a lot of time had passed, maybe 10 or 11 years since we had done anything that we called “Star Trek” together. It seemed appropriate that there would be a difference in the setting and the costumes. All of that made sense to me, and I think we adapted to that fairly quickly.

Kelley: (The new costumes) were all horribly expensive and the shoes were sown down on the legs of the trousers. (He laughs.) We all had to have a special man come in to help us get into them.

Sloane: Is there an incident or story making this movie that stands out in your memory?

Nimoy: I think one of the saddest aspects of the making of that movie was that we had lost our sense of humor within the story (and) within the characters and the relationships. One of the things that I think our viewers had always enjoyed was this twinkle-in-the-eye humor that was a very important part of “Star Trek.”

On the last day of shooting, when the problems of the story had been solved, and the assumption is that we’re all going to go our separate ways, Captain Kirk says to Dr. McCoy, “I’ll drop you off on Earth.” McCoy says, “Well, now that I’m here I might as well stay.” Then Kirk turns to Spock and says, “We’ll have you to Vulcan in a couple of days.” During the rehearsal—it wasn’t written— I said, “If Dr. McCoy is to remain onboard, my presence here will be essential.” Everyone laughed, because it suggested the ongoing fencing between Spock and McCoy that had always been traditionally part of the fun and humor of “Star Trek.”

I saw the producers and director Robert Wise in conversation, and Wise came to tell me the decision was that it would seem that the humor was uncalled for. That was pretty much the way it went for the whole movie. It was the one moment that seemed to optimize that frustration.

Sloane: The premiere was held at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. on Dec. 4, 1979, What was it like seeing it on a big screen for the first time?

Shatner: It was a fantasy come true. The opening night of the film was a big deal. We were in Washington and there were searchlights—the whole Hollywood opening.

Kelley: Like the audience, I was in awe of some of the special effects. I felt the opening would never end. It went on and on and on. I thought I was in Disneyland looking at an exhibition of a new film technique.

Sloane: Why do you feel “Star Trek” has had such a lasting legacy?

Shatner: I think that “Star Trek” may be edifying a mythology that we don’t have in our modern culture because it’s so fractured. I think our lack of mythology perturbs us, even unconsciously, in trying to deal with the world around us. Perhaps “Star Trek” is dealing with a world that is not around us yet. Maybe we supplied a kind of myth that is “mything” in the modern culture.

Nimoy: Anything that starts on television in 1966 and has spawned what it has over the years is a phenomenon in our industry. Our terminology is in the culture: “Live long and prosper” and “Beam me up, Scotty” are in the culture. Can I tell you what it means to the world? No, I think that’s for others to decide.

In the best of “Star Trek,” there is an amazingly intriguing story, without necessarily terrible people portrayed as the villains. There is not a shot fired at anybody in an attempt to injure or kill anyone. To me, that was what we were able to do best.

A lot of science fiction and adventure films trade in shoot-em-ups, explosions and destruction that are awesome, and I admire the skill in doing it—but what we had was unique.

Kelley: If I really knew it, Judy, I’d bottle it. We touched a chord with people. I think it began to show them that there was a future, that there was much to be done. They saw these people who were very professional, each caring for each other, and a show being able to say certain things that couldn’t be said at that period of time. And, as it ages, film has a funny way of becoming classic.

Portions of this interview were first published in Film Review Magazine.