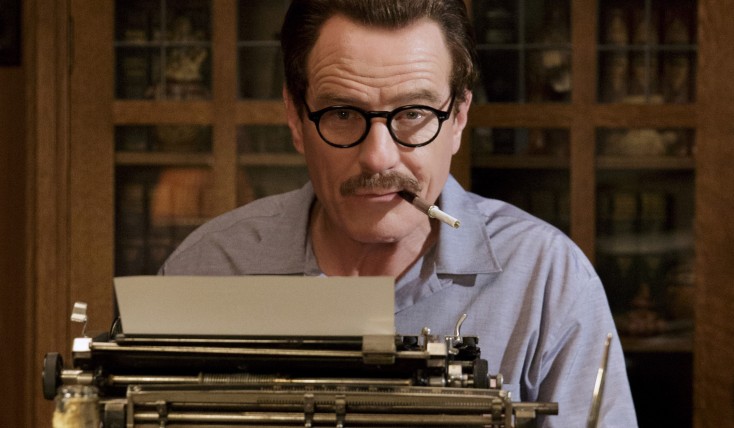

Bryan Cranston (left) stars as Dalton Trumbo and Diane Lane (right) stars as Cleo Trumbo in Jay Roach’s TRUMBO. ©Bleecker Street. CR: Hilary Bronwyn Gail/Bleecker Street.

By ANGELA DAWSON

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Though few outside of the Hollywood community know the name Dalton Trumbo, the two-time Academy Award winning screenwriter stands as an example of someone who stood up against censorship during the turbulent Cold War era, when paranoia ran rampant, and prevailed.

Bryan Cranston, best known for his Emmy winning role as high school teacher-turned-crystal meth kingpin on “Breaking Bad,” delivers another noteworthy performance as the outspoken and flamboyant scribe who took on the conservative Hollywood power structure that blacklisted him and other (mostly) writers who were labeled communists, and therefore un-American, in the 1940s and 1950s. Cranston blends into the role of the outspoken and steadfast writer, who lost a lot, his reputation and his beloved Los Angeles area ranch, for standing up for his rights and his beliefs.

Even before he won his Oscar statuettes, Trumbo was nominated by the Academy for his drama “Kitty Foyle.” But because certain Hollywood individuals could not tolerate other people’s political views that differed from their own—namely influential gossip columnist Hedda Hopper and silver screen legend John Wayne—Trumbo and others were blacklisted, and subsequently unable to get legitimate work in their chosen field for more than a decade. They, instead, wrote under pseudonyms or had other non-blacklisted writers front for them. They were publicly humiliated in Congressional hearings (the House Un-American Activities Committee) as part of its sweeping probe of communist activity in Hollywood, and ordered to name names. (Most of them didn’t.)

Though Trumbo co-wrote “Roman Holiday” with John Dighton, the co-credit went to Trumbo’s friend Ian McLellan Hunter. It wasn’t until decades later (2003) that the writer was finally acknowledged for his part in writing the screenplay, and awarded an Oscar posthumously. He earned a second Oscar for writing “The Brave One,” in which he used a pseudonym. It was only after megastar Kirk Douglas insisted publicly that Trumbo get screen credit for writing 1960’s swords-and-sandals spectacle “Spartacus,” that the blacklist ultimately met its demise.

Fresh from his Tony-winning performance as 36th president Lyndon Baines Johnson in the play “All the Way,” Cranston immersed himself in this other larger-than-life character who would often pen his scripts in the bathtub, smoked like a chimney and never backed down from his ideals.

The drama is directed by Jay Roach (“Meet the Parents,” TV’s “Game Change”) from a script by John McNamara (“Prime Suspect”), and based on Bruce Cook’s book, “Dalton Trumbo.” Starring alongside Cranston is Diane Lane, John Goodman, Michael Stuhlbarg, Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Louis C.K., Elle Fanning and Oscar winner Helen Mirren (who plays the wickedly influential Hopper).

Cranston, 59, spoke about finding the voice of Trumbo and the writer’s legacy and relevance of his (and his fellow blacklisted individuals) experience today.

Q: When you got the script, what was your first impression? How did find out you got the part? Why did you decide to do it?

Cranston: The script is always the first thing that attracts an actor, the story and the script that supports it. And they don’t often go together. Sometimes you have a great story and the script kind of falls short of realizing the full potential, or vice versa. This was A-plus on both of those. I always then look at the character, and this character was phenomenal. It was huge and dangerous and scary and all that, and important. The next is the director and the other cast. You wonder, who else you’ll be playing with? It’s an important factor to take into consideration. Does the director have the sensibility and sensitivity to explore and able to navigate a bunch of actors with different ways of approaching the work? There’s no one-size-fits-all. It takes a very sensitive, insightful person to do that. (quips) Despite his lack of those qualities… we looked for that but couldn’t find it. So in talking to Jay, it was an easy “yes” for me.

Q: There is a distinctive way that Dalton Trumbo spoke and the way that he looked. How did you find his voice?

Cranston: It really had a double entendre to that: the voice of Trumbo. There is a lot of source material and videotapes and audiotapes on that. But you can kind of get lost in that and if you only focus on that you could start down a road of interpretation. I wanted to be very careful not to do that. That being said, he was a very flamboyant character with contradiction, irascibility and passion. He was very prolific. He was a beautiful, wonderful big character and dramatic. So it’s kind of an amalgam of research (I did), from reading the books about him to talking to the people that knew him. It was almost like being a detective assembling clues.

Every time I start a show or a character, it’s always outside of me and I always envision him out there somewhere. I feel like the more research I do and the more I talk to people and go back into the script, the closer (the character) gets to coming in, and then at some point you just have to have trust in and have faith that he becomes a part of you—not just the sound of him or how he carries his body, but his sensibility and his point of view, and that sort of thing. Then, once that happens, it’s great because when you talk to someone, and other actors will say this to, is that when we rehearse and talk about it, the actor playing that role will have a specific point of view. I point to Diane (Lane, who plays Trumbo’s wife, Cleo) because we had this conversation, and she will say, “Well, I need this. This is what I’m going for.” And the other actors will voice their concerns at a family dinner table and it’s up to Jay (Roach, the director) to keep everybody alive and make sure that everybody’s thoughts are heard and understood and incorporated.

Q: Is this story a cautionary tale about state-sponsored censorship?

Cranston: I think embedded in the story is definitely a cautionary tale. The film, first and foremost, is entertainment, and I think through entertainment we will have more people possibly taking the message that is behind it. I think anytime that a government sets out to oppress civil liberties that the citizens need to be very concerned about that, speak out, and stand up for their rights. So that is the cautionary tale. Hopefully, this generation, the younger generation, will be able to learn by that and remember that, and see its parallels when they pop up. Jay (Roach, the director) pointed out very astutely last night that some people may equate what happened during the point of the movie to the Benghazi hearings now—spending millions and millions of dollars and months and months of time and energy and focus. (sarcastically) But it’s not political. And so, that’s overreach. That’s a suppression of people’s civil rights. So it’s there. It’s out there to be experienced.

Q: You’re playing someone who the public hardly knows so was it important to get him right or just capture his spirit?

Cranston: I think when you approach a character you look at it almost like a funnel. You have to stay open. You don’t really know what you’re looking for. And you just take it in, take it in, take it in and trust that your instincts will grab hold of something. You may not even know why. You keep collecting these things and internalizing them, so that’s what starts to generate the development of the character. It starts to go through a funnel and what comes out is your specific interpretation of that character. I guess some actors can just do a straight pole, where they know exactly what they want to put in and exactly what they want to take out. I don’t trust myself to say, “Oh I know exactly what I want to do and I’m going to do just that.” So I just open up and try to take in as much information.

Q: What was the most challenging part for you in this film since you had to smoke a lot and soak in the bathtub for hours?

Cranston: (joking) The challenge of working in a bathtub is not to get pruney fingers and not to drink too much before you get into the bathtub. You know what I mean? It becomes very pragmatic when you think about it. Also, after a while there, you kind of sheepishly ask, “Can I have another bucket of hot water?” Because the bathtubs we used they weren’t a part of those bathrooms. We brought those tubs in so we just plugged up the drain and they had to fill it with— hopefully—hot, soapy water, and then you discreetly place that desk so that no one sees something they shouldn’t. Believe me no one should see this.

Q: What about the chain smoking?

Cranston: I stupidly thought that I wouldn’t smoke real cigarettes. I thought, “I’ll protect myself from ingesting nicotine and tar and all the carcinogens. But then I realized I’m still inhaling smoke. I’m still smoking these herbal cigarettes. There were many times when we were looking for places that I wouldn’t have to smoke. But if you have a cigarette in your hand and you’re playing that character, even if you are off screen, I’m not focusing on not inhaling, I’m focusing on doing the scene and so I catch myself inhaling even off screen. So it became an issue a little bit. I was getting hoarse and not feeling great. But Mitzi and Nikki (Trumbo’s daughters) said, “Oh, dad was a chimney. He often lit one to the other,” as we’ve known some people to do, so it was a challenge. It was more of a physical challenge.