By JUDY SLOANE

Front Row Features

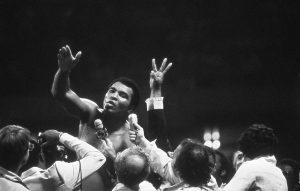

HOLLYWOOD—PBS’ “Muhammad Ali” spotlights the life of the three-time heavyweight boxing champion and activist who ruled the ring with power, charm and humor… and focuses on his outspokenness outside of it. With insights and memories from friends and family, plus archival footage and photos, the series includes his great bouts, “The Fight of the Century” and “The Thrilla in Manila,” both against his rival Joe Frazier, and “The Rumble in the Jungle,” where he defeated George Foreman and regained his heavyweight title. Also highlighted is Ali’s personal life, his Muslim faith and his refusal to join the army to fight in Vietnam for religious beliefs. Subsequently, he was banished from boxing for three-and-a-half years.

The four-part documentary by the iconic filmmaker Ken Burns, will air on PBS Sept. 19-22, from 8 p.m. to 10 p.m. (Check local listings.)

Muhammad Ali’s daughter, Rasheda Ali, an author, actress, spokesperson and Parkinson’s disease advocate, joined the TV Critics Association to speak about her father’s life. Her book, “I’ll Hold Your Hand So You Won’t Fall—A Child’s Guild to Parkinson’s Disease,” was inspired by her father, who was afflicted with it for 30 years.

Q: When the public saw Muhammad Ali, he was usually “on” and quite hyper. When he was away from the camera, was he able to turn it off and remain calm when he was home?

Rasheda Ali: Daddy was on stage when he was fighting. He really pretty much put on a show for all of the people that tuned in who were not there live. He even said, “I want to give people their money’s worth.” So, whether it was jiving with Joe Frazier or (George) Foreman, he really put on a show, and he promised he would do that.

In the privacy of our home he was the same person he was on stage, but he was so sweet and cuddly. Daddy was very affectionate. I think all of us are (affectionate) now because of him. We gave each other lots of kisses; so much love.

You can’t take that sweet man out of the boxer. He was an animal in the ring, but he was a sweet man to others, not just us. He served others his whole entire existence. Daddy was a gentle giant, for sure, and he loved for us to play games with him and read the Qur’an to him. And he shed a tear at home when we would read something that resonated with him that was really deep and spiritual in nature.

Q: I can’t imagine what it was like knowing you had to share your father with the world. Can you talk about just how you came to deal with that?

Ali: I get this a lot. What was it like being the daughter of Muhammad Ali? First of all, there are nine of us, and each one of us experienced very different emotions when it comes down to that.

When I was younger, probably around kindergarten, I knew my dad was not just a regular dad. My daddy came to our elementary school and everyone stopped, the teachers didn’t teach and the principal was, like, drooling. I (thought), “This is not just a regular dad.” I knew then (he was) everybody’s dad.

I was pretty selfish in my attempt to try to grab him only for me at a young age. As I became older, I started to embrace the sharing because I realized how much good he was doing for so many millions of people. I started to realize my daddy was bigger than boxing [and] why he gave so much of himself, because he saw there was a purpose in life.

Q: The public perception of your father and the private perception of your father must be two entirely different things.

Ali: My dad lived in a time where there wasn’t social media, things weren’t broadcast all over the world in the sense that we’re familiar with. The time of my dad’s and my mom’s divorce, my dad would have been Public Enemy No. 1 in our time, because (of) his relationship with my mom and how that all unfolded. Daddy wasn’t real respected from the public when he left my mom, and we as kids weren’t happy with that either.

I’m not giving him a pass for his philandering, but I will say that there were a lot of people around my father who weren’t positive forces in his life. (My siblings and I) were like, “Daddy is a good-spirited person, but he made mistakes.” My dad always owned up to his mistakes. Naturally we were more forgiving and we understood the circumstances that my dad were under, were very unique in nature.

Q: In Ali’s later career, following the “Thrilla in Manila,” he continued to take on fights against inferior opponents even though he was medically advised against doing that. He obviously had nothing left to prove in the ring at that point. What was his motivation?

Ali: Do you know what I really think? I’ve always said that my dad loved boxing so much. He (was) boxing since he (was) 12 years old. He definitely stayed in the ring way too long. It was one of those things where, if he wasn’t diagnosed with Parkinson’s or Father Time didn’t creep on him he would still do it because his passion for boxing was so clear.

My dad couldn’t say good‑bye to boxing; boxing had to say good‑bye to him. There’s two parts as to why he stayed. One (was) his love for boxing; he didn’t want to let it go. The other is that the people in his corner, no pun intended, wanted him to continue boxing because he was basically their ATM.

Q: Do you have one piece of memorabilia from your father that you treasure the most?

Ali: Yes. At the time of his passing, my son gave my dad some prayer beads. We were praying over him and we had an imam in the hospital in Scottsdale praying. My dad held the prayer beads in his hands as we prayed for hours and hours on end, and those prayer beads mean so much to us.

My son Nico owns them. He could not touch them with his bare hands because it was the last thing that my dad held in his hand. He grabbed the prayer beads with gloves, and he frames it to this day because it was the last spiritual, emotional connection that we had with our father. To be sent off in prayer was one of the biggest blessings that you could ever give to any human being in life.