By JUDY SLOANE

Front Row Features

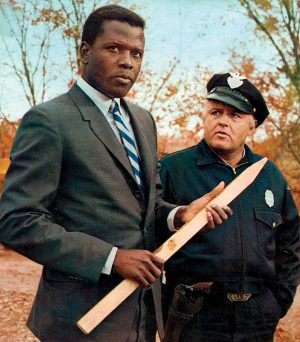

HOLLYWOOD-In 1967 at the height of the Civil Rights movement in America, a thoughtful movie about the volatile relationship between a black homicide detective, Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier) and a white bigoted police chief, Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger) swept the nation. It was called “In the Heat of the Night.”

Based on the novel by John Ball, and set in the deep South in the racially charged town of Sparta, Mississippi, the movie tells of the murder of a wealthy industrialist, Philip Colbert. At the crime scene Gillespie realizes the victim’s wallet has been stolen and dispatches one of his men to pick up any suspicious characters. The officer apprehends Virgil Tibbs waiting for a train at the railway depot, with a wallet full of cash, bringing him back to the police station. On being asked by Gillespie how a black person could earn that much money, Tibbs declares he’s a police officer from Philadelphia. From that moment on, Gillespie and Tibbs grudgingly work together to solve the murder gradually developing a mutual respect for each other.

In April, 1995, I went to Rod Steiger’s house in Los Angeles to speak with him about the movie and the late actor’s long friendship with his co-star Sidney Poitier.

Judy Sloane: When you first read the script, did you know immediately that you wanted to do it?

Rod Steiger: I was married to Claire Bloom then. Up until then I’d been doing strong people who are ruthless, and I threw the script across the room and I said, “Claire, I’ve got a good chance to be nominated.” She said, “What are you talking about?” I said, “This is a good guy. I get a chance to play a nice person!”

You’ve got to remember, the foundation of prejudice is the absence of knowledge. The intellect is not worth very much compared to instincts. Instinctively these men begin to respect each other.

I always thought of them as two gunfighters who respected each other and gradually came closer and closer together because of the fact they there was no prejudice when they were in action.

Sloane: You and Sidney have enjoyed a long and abiding friendship that began in New York twenty years before you made this movie. Did he have any worries about doing the film?

Steiger: He was worried about the prejudice down South, which I can’t blame him. I said to him, “Sid, we’re going to be together, we’ll have our suites together with a door open between.”

Sloane: Did everything go okay?

Steiger: (One night) there’s a knock on my door and there’s a kid about 17 years old crying with a double-barreled shotgun, and he’s drunk. He says to me, “I’m looking for my wife.” And the first thing I think of is Sidney in the next suite. So I got very jaunty-jolly and said, “Come on in, look around,” praying he does not see the open door. He’s halfway out and he says, “What’s that?” And I’m saying (to myself) “If Sidney is in there with a lady this guy is going to blow him away before he finds out he made a mistake.” I said, “Please let me go in and wake up Mr. Poitier.” I woke Sidney up and the guy came in. Then he apologized to Sidney, he apologized to me. He left and Sidney and I just sat down on the couch, and I said, “Thank God you weren’t entertaining anybody, Sidney!”

Sloane: I think one of the most memorable characteristics of your character is the way he chews gum.

Steiger: I said to Norman (Jewison, the director) “What’s with the gum? It’s such a cliché. I don’t want to do that.” He said, “Do me a favor. See what you can do with it. I like it.” As we were rehearsing I realized that through the gum I could tell you the inner workings of this man. When he chewed fast you knew he was getting mad, when he didn’t know what to do it slowed down, if everything stopped he didn’t know where the hell he was.

Sloane: You and Sidney improvised a scene that would take place in Gillespie’s house, where you talk about women, loneliness, your work. What do you remember about that scene?

Steiger: (It reminded me of) one night when Sidney and I were on the town together and we came back to his apartment, this was way before “In the Heat of the Night,” and we almost duplicated the scene in the sheriff’s house. We were both very tired and getting grouchy. I said to him, “You know, Sidney, fatigue is a terrible enemy of common sense and intelligence and when I’m tired like this and if you got me angry, I could see myself saying something racial and I can see you saying something racial back to me.” And it was funny years later when we did it in the picture. That scene is my favorite.

Sloane: What was it like acting opposite Sidney?

Steiger: I think he’s miraculous. He’s a fine actor, but why I say miraculous is you’re talking about a man who learned to speak well by listening to the radio, whose parents were tomato farmers. If you talk about a self-made man this is one of the prime examples. Sid and I used to talk. The one thing he didn’t want to be was considered the prince of his people. He didn’t want that responsibility, and I don’t blame him.

Sloane: I heard that you and Sidney snuck into theatres after the movie had opened.

Steiger: Sidney and I used to sneak into the theatres to see this moment of history. Sidney’s in the greenhouse and the white man slaps him, and for the first time in the history of film the black man slaps back. We could tell how many black people or white people were there because the black people said, “Go get him, Sidney,” and the white people were gasping.

Sloane: The movie won Best Picture at the Academy Awards and you won Best Actor. Do you remember what you said that night?

Steiger: I said, I want to thank Norman Jewison. I want to thank everybody in the picture, but most of all I want to thank Mr. Sidney Poitier who taught me about prejudice and maintaining dignity under prejudice. Sidney, we shall overcome.

Portions of this article were first published in Film Review Magazine