By ANGELA DAWSON

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—It’s not often that you’ll see Johnny Depp in a film where he isn’t playing some larger than life costumed character. In the documentary, “For No Good Reason,” the internationally acclaimed star is just himself, and he serves as a guide into the world of one of the most influential British artists of the counter-culture movement, Ralph Steadman.

Depp and Steadman are mutual friends of the late iconic writer Hunter S. Thompson, and Depp unobtrusively leads the viewer on an intimate portrait of the artist at his home in Kent where he is still creating mind-blowing works of art.

Steadman, who illustrated many of Thompson’s writings, including his “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” opus and unforgettable journalism assignments, speaks about his friendship with the writer, his love for art and his passion for civil liberties in a riot of stories and images compiled over a 15-year period by director Charlie Paul and his producer-wife Lucy Paul.

The Pauls, who operate a video production company in England where they produce music videos and commercials, had unprecedented access to the artist’s library, friends and collaborators to create the documentary. In addition to Depp, other famous friends of Steadman’s appear or contribute to the film in some way, including filmmaker Terry Gilliam, actor Richard E. Grant, and musicians Slash, All American Rejects, Jason Mraz, Ed Harcourt and others.

Charlie and Lucy Paul, an enthusiastic and charming couple, recently spoke about making this labor of love to a man that profoundly affected their passion for art and film.

Q: Have you been working together throughout your career?

Charlie: Yes. Lucy and I have had our current production company about 15 years. We’ve been married for 25 years so are very much aware of each other. It was a tough decision to be working with your wife, especially as a director because I’m bullish. I make ridiculous demands. I said, “I want Johnny Depp in my film. Can you sort it out, Lucy?” Normally, in a working relationship you might spend eight or ten hours working together, but we spend 18 or 20 hours a day of consciousness together so you can work out a lot more. It’s actually been really productive.

Q: How did this turn into a 15-year project?

Charlie: I never wanted to wrap the film up. I was making a film with my hero and I just enjoyed the process. I was collecting stuff as I went along and I was making segments that could hold together, but then Lucy said, “Look, we’re going to have to put a time-scale on this.” That’s when I got a little bit more pressure because I had no idea how I was going to finish this thing up.

Q: You incorporate a lot of different film styles in this including animation and motion control, where single frame images are strung together. Can you talk about that?

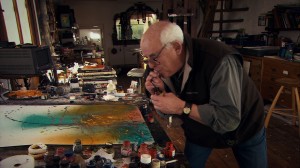

Charlie: When I went down to Ralph’s studio, I set a digital camera up above his desk, and I rigged it all up with lights and a button. So when he went into his studio, all he had to do was press the big button and the lights would come on and the camera would energize and every time he did a brush stroke and painted, he’s reach up and took a frame (with the camera). Ralph works very hard; he’s very prolific. So every week he’d ring me up and say, “The camera’s stopped working,” which meant the chip was full. So I had to go down (to his place) and take the chip out and put a new chip in. We’d do a day’s filming and then I’d go back to my studio and look at the contents of his chip. It would give me insight into all of Ralph’s work from the previous week. I’d have all these JPEG’s of these images building up. I could never leave Ralph a day without that camera working. If he suddenly decided to do five pictures in one day, I’d have to go down there the following day and clear the camera out. That was the driving force; I could never let go at that stage. By then, I knew I’d bought the ticked and I was in for the ride. I had to go with it. So that was a marvelous way of me keeping Ralph on board, and Ralph wanting me to come back and sort out the camera.

Q: How difficult or easy was it to get the participation of the actors and musicians involved with this?

Charlie: Everybody in the film knew of Ralph or knows him. Richard E. Grant felt indebted to Ralph because on Richard’s first big film, “Withnail & I,” he remembers Ralph going to set and taking photographs and turning to Richard and saying, “You’re the man! I know you’re the man!” That gave Richard the courage to play the part. And the same with Terry Gilliam, who I first realized would be a great contributor because on the wall of Ralph’s studio is a painting from “Monty Python,” with a little note from Terry saying, “I owe you more than you could ever imagine.” Terry told me that when he first came to England, Ralph was the one artist he wanted to be like. He practiced splattering like Ralph does. So all the contributors had a personal history with Ralph that we could develop and bring back in. The same goes for musicians, like Ed Harcourt. We asked him if he would get involved and he said, “Of course, I’ll get involved!” He lifted his shirt and on his back he has a massive Gonzo fist tattooed there. The All-American Rejects recorded a track called “Gonzo,” because they love the whole thing. Ralph had done art for Slash’s album so Slash was happy to let us use his music. We were lucky to have a subject in our film, who had affected so many talented people in so many different ways. All we really had to do was reach out to these people, and it was just down to timing.

Q: How long did you get Johnny Depp involved?

Lucy: Johnny had been aware of the project for quite a number of years, really. With his involvement, it just a case of whenever the poor guy has time because his schedule is hideous. I don’t know how he does it. Also, the process in which we filmed with Ralph has always been a small, intimate thing. That needed to be the case with Johnny as well. Ralph’s studio is about an hour and a half out of London. When Johnny was in the UK, he’d just get in the car with his lovely, trusty assistant, and turn up. It was last minute, because that’s how it works. That suited us just fine. We’d just go (to Steadman’s) and Charlie would film. On one of the days, he did have a couple of the cameras and cameramen, but they were all people who had worked with us on other days at Ralph’s studio.

Charlie: By the time we had Johnny involved, we already knew what we didn’t want to shoot. We were precise about the subjects we were going to cover.

Lucy: Johnny just gets it. It’s quite funny seeing them work together, because when you point Ralph in one direction, guaranteed he goes the other. Johnny just had this lovely gentle way of navigating the conversation back. He was great. He was really great to work with.

Q: Did you give him questions to ask Ralph or did he come up with them himself?

Charlie: Johnny’s fascination with Hunter (S. Thompson) and that whole relationship thing already had been established. It gave him a lot of connections already. You’ll notice that the film is made up of segments and each segment involves a particular body of work of Ralph’s. We already had worked out that “Fear and Loathing” was going to be a subject, and the (Thompson and Steadman’s coverage of the) Kentucky Derby and the Rumble in the Jungle (fight) would be subjects. We knew what we wanted so we wouldn’t spend weeks with Johnny doing stuff that would never make the cut. We were lucky that the strong material already had risen to the surface. It was a matter of reintroducing that into the filming process with Johnny and Ralph.

Q: How long ago did you shoot his segment?

Lucy: Two to three years ago.

Charlie: What was so fortunate about the film, because it was made under the radar and out of commission, in a sense, we were able to take our time. We sat on this film a year after (we finished) to make sure everything stuck, and nothing was falling away. There has been a period since finishing the film where we have been tinkering with the music and stuff.

Lucy: I think Johnny has had two movies come out since he finished working with us. (She laughs.)