By ANGELA DAWSON

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Danny Elfman has composed the music for 17 of Tim Burton’s films, ranging from “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure” to “Beetlejuice” to “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” to “Alice Through the Looking Glass,” and the list goes on.

The L.A. native’s latest pairing with the iconoclast filmmaker is the new incarnation of the Disney classic “Dumbo.” While it’s easy to presume that Elfman finds the process easy after nearly four decades of working with filmmaker, he points out at a press day that it’s quite the contrary.

“I still never know what to expect from Tim at all,” the prolific composer says. “People think, ‘Oh, you must have a shorthand, where it’s really simple,’ and I go ‘No, actually, working with Tim is a lot less simple than (working with) a lot of other directors.’ His mind is strange and interesting. I learned many years ago never to take for granted what I think he’s going to want.”

With “Dumbo,” a CGI/live-action hybrid that tells the heroic story of a little circus elephant with oversized ears that give him the ability to fly, Elfman began with a simple theme for the creature, and expanded the score from there. The film stars Colin Farrell, Michael Keaton, Danny DeVito, Eva Green and newcomers Nico Parker and Finley Hobbins, as circus children who take the exploited baby elephant—cruelly separated from his mother—under their wings.

Once the frontman for the ‘80s rock band Oingo Boingo, Elfman, who also famously composed “The Simpsons” and “Desperate Housewives” theme songs, reveals that he didn’t set out to be a rock star. He always intended to be a film composer, but took a detour for a bit, before returning to his passion.

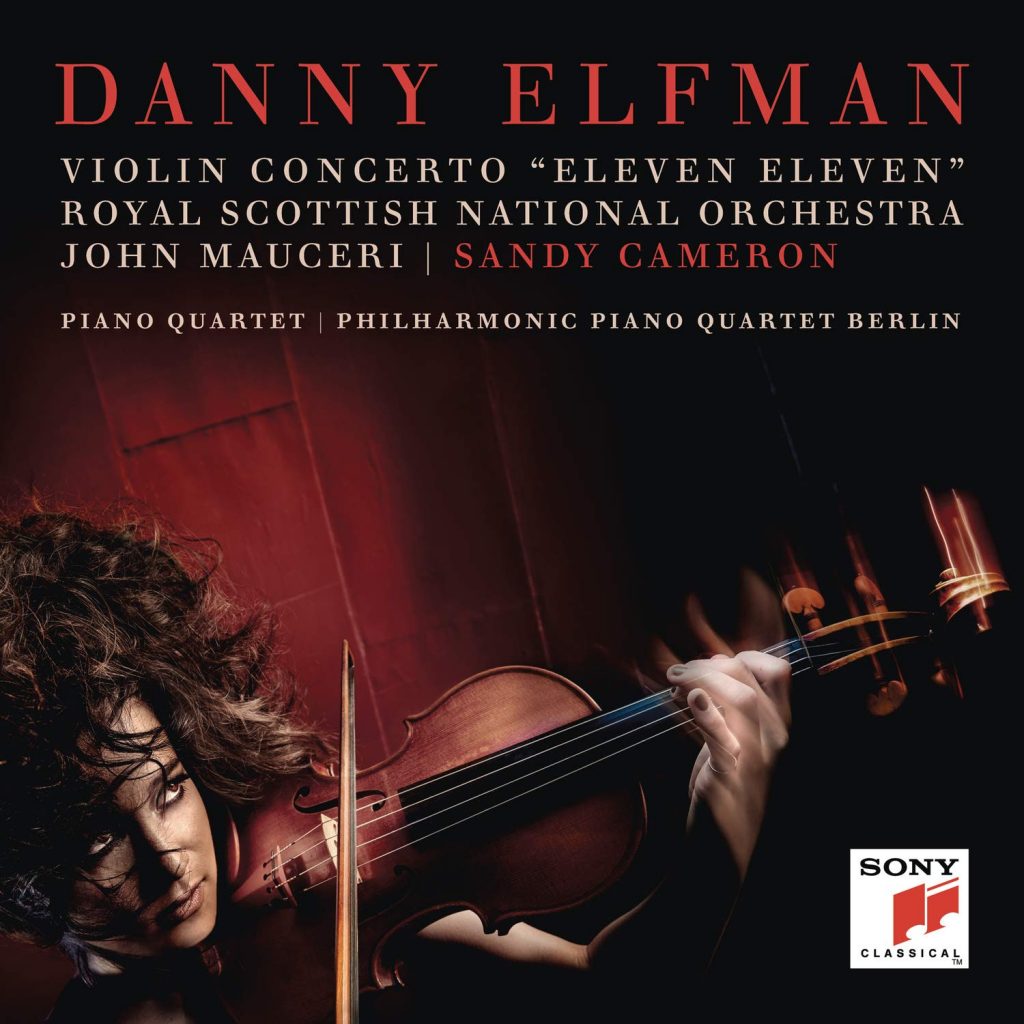

As the highly anticipated March 29 theatrical release of “Dumbo” approaches, the industrious composer also releases his first ever violin concerto album titled “Eleven Eleven.”

That project began two years ago, when the Prague orchestra asked him to compose a violin concerto for violinist Sandy Cameron. Elfman responded by composing the concerto as his first freestanding orchestral work. The album, available Friday March 22 on Sony Classical, is performed by Cameron, with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra conducted by John Mauceri. The opening movement of the violin concerto “Eleven Eleven” has been compared to the famous “Metamorphosen” by Richard Strauss. His second work on this new release is titled “Piano Quartet,” and also has movement titles such as “Kinderspott” (Scorn of Children) and “Die Wolfsjungen” (The Wild Boys).

At the “Dumbo” press conference, the focus was on Elfman’s longstanding association with Burton and his visionary, unique films and their unique accompanying sound.

Q: In terms of writing these scores versus writing music for your own albums, how is your process different? For “Dumbo,” you’re writing to please Tim but when you’re writing other types of works, such as the classical music album, is that different?

Elfman: I started out as a film composer so I didn’t start out writing orchestral music for myself. I had never heard an orchestra play until I heard “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure.” I literally had never stood close to an orchestra or dreamed that I would. My upbringing was film music. I always intended—when I was a teenager—to work in film, not music. I didn’t take lessons and I didn’t play any instruments. The two things in film I never expected to do was act because I knew I couldn’t act, and music because I didn’t really do music. It’s just weird that it worked out that way.

I wanted to be an editor, a writer or a cinematographer—anything but music. So, that’s what I ended up doing. It was really over the course of these years writing for orchestral scores that I began to feel more of a need to write outside for concert stage.

Mainly, because when I started doing Elfman-Burton shows. We started touring these all over the world—doing full concerts of essentially 15 scores reduced down. I saw that there was this hungry audience that was coming to see the orchestras play. I felt that there is a world that can bring classical music listeners and film fans together. There were two separate audiences, but there shouldn’t be. So, I got motivated to start writing concert pieces that would possibly bridge these audiences.

I remember when we were at the Lincoln Center playing, and this guy was there from the Met. He said to me, ‘God, I would kill to get this audience into the Met,’ because our audience tends to be a younger and very energetic audience.”

So, it was really in the process of doing these concerts of Tim’s music that I started to get this idea of writing concert music, which I needed to do for myself anyhow.

Q: Discuss how you and Tim Burton work together? Do you create the score first?

Elfman: It’s always a kind of roundabout process. When we start the film, he’ll say very little about the music. We have a thing called a “spotting session,” where we go through the whole film top to bottom and break it down into all the musical parts and give them all a name and a number. If the movie is 1-3/4 hours long, the spotting session will be 2-1/14 hours. If the movie is two hours, (the spotting session) will be 2-1/2 hours. It’s quick. He doesn’t want to talk about it. When there’s music to hear, then he’ll talk. This is something that we’ve learned together. Talking about it beforehand doesn’t actually get us anywhere. He’ll respond to what he hears. Then, I’ll do a lot of ideas and I’ll get a sense (of what he wants).

One thing I do have to say is when I got the call about the movie, this is one of the first questions I always have, is Rick (Heinrichs, the production designer) and Colleen (Atwood, the costume designer) on the project? And if it is, I’ll say, “yes.”

Unlike other films I’ve done with Tim, (“Dumbo”) was way in advance. It was like almost a year from when I was going to start. I went back to work on whatever movie I was working on. (But) I had a little theme in my head. I didn’t know a lot about “Dumbo” (the original 1941 Disney animated film). I didn’t see it as a kid. I knew that baby elephant loses his mom so I knew that it was going to be bittersweet, sad, and I had a musical idea.

Before I started, I wrote it (down), played it, finished it and then put it away. I’ve never done that before with Tim beforehand. A year later I came back to it. It was kind of a unique moment that I hadn’t experienced.

So, it’s always going to be a real interesting process musically getting to wherever we’re going to get. I just never know where that’s going to be. Usually, it’s something that we have to find in process. It’s a good way to work, actually, because when directors say what kind of music they really want, it usually ends up being not at all what I’m imagining. It’s all mystery.

Q: Do you have a special attachment to the music you’ve made for Tim Burton’s films?

Elfman: Yeah. Most of my favorite scores that I’ve written out of over 100 films, most of my favorites will have been Tim’s movies. I won’t say that many of those weren’t without great challenges. Finding where that was can be really challenging with Tim but I don’t care. If I like the result, whether it was like a slam dunk or it really took a long process to find, it becomes irrelevant to me. It’s only the end-product that matters. It’s all you remember later, anyhow. It’s kind of like having kids. If you remember the first year, you never want to look at another kid again.

I find film scores to be somewhat similar. In the middle, I often say I’ll never do this again. I’m done. Then, at the end, if it came out well, then I go “Yeah, sure, I’ll do this again. It wasn’t so hard.”

Q: How did you hear the theme for Dumbo, and compare and contrast it with other scores you’ve written?

Elfman: I don’t really know. When I wrote “Dumbo’s Theme,” I wrote it as a bittersweet sad theme because that’s always what makes me excited. The sadder it is writing it, the happier I get as a composer. But I do try to put my themes through a bit of an acid test. If I have the melody I like, can I make it triumphant? Can I make it quirky? Can I make it silly? It’s like I’ve got to put it through each of these things. Whatever it is going to be asked to do, I need to know that it will do that. I don’t want to find out when I get there that the music just doesn’t want to get big or triumphant. That’s part of my process. It’s like I have to put it through all those things. And I learned. When it gets big, it’s going to go this way. It’s going to do this. I didn’t know at that point there would be quite as much triumph. Very early on, Tim was like, “I like that.” Whenever Dumbo is in the air, he would say, “Do that thing.” I’d go, “Really? Don’t you think we should…”? And he’d respond, “No. Do that thing.” He was very specific.

So, it’s like once I hit on that once, Tim really caught onto that moment. He really wanted to bring it back. We redid a couple of cues. The word he used the most in the score was “soaring.” He really wants to make sure that Dumbo soars. And I said, “But don’t we want ‘Dumbo’ to be heartbreaking?”

There will be one element of the thing that he’s really focused on and, to the rest of it he’ll say, “That’s fine.” Sad stuff is all fine. Having not seen (the 1941 original) as a kid, I didn’t have a lot of attachment to it.

When I got the call from Derek (Frey, the producer) about doing it, I watched it. It’s the first time I had ever seen it from beginning to end. What was crazy was, (the song) “Pink Elephants on Parade.” I know that really well. I don’t know how I knew it. But I did. “Casey Jr.”—of course I know that. How do I know that? I didn’t see it as a kid. There are all these elements I was hoping we could work in. The thing that excited me the most was that it’s going to be some heartbreak in there. That’s really where I get my jollies.