By JUDY SLOANE

Front Row Features

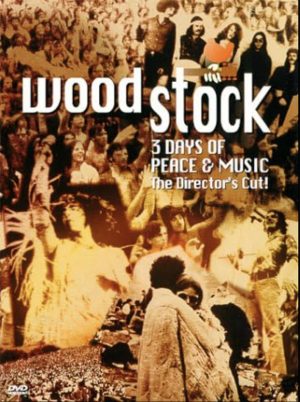

HOLLYWOOD-Between August 15-18, 1969, an extraordinary event took place on a 600-acre farm in Bethel, New York. The Woodstock Music and Art Festival, truly a legend in its time, epitomized the ideals, beliefs and vibrations of a generation. The producers brought in John Morris, who had run Fillmore East, a successful venue for rock concerts, to oversee Woodstock.

Director Michael Wadleigh, was a social political filmmaker in 1969, doing experiments in fusing rock and roll into films about civil rights and American Indians. The movie opened on March 27, 1970, to exceptional reviews, and went on to win the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

I spoke with Michael Wadleigh and John Morris in 1995, about their memories of the iconic music festival.

Q: John, how did you organize for so many people?

John Morris: (Producer) Mike Lang and I had a bet that I would give him a thousand dollars for every thousand people over 50,000. But that was a safe bet, because nobody had ever put 50,000 people in a place before. We had settled on a town called Walikill and gotten blown out of there by a fairly rabid group of people who suddenly changed the laws on us. So we moved it on the Bethal site. Max Yasgur, who had the farm, read about our plight in the New York Times, tracked us down and called up and said, ‘I’ve got a farm, come have a look.’

Q: The first day of the concert created a crisis, over 500,000 people turned up in the ten square mile tract, and the Governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, threatened to send the National Guard – what did you do?

John Morris: I spent the first five hours Friday morning arguing with his Chief-of-Staff on and off, convinced that the man was about to cause what he later caused in Attica (a riot). We won the argument, thank God.

Q: How did you get the stars to the venue with the roads being so jammed?

John Morris: I literally turned around to my then-wife and said, ‘Take the Yellow Pages and hire every goddamned helicopter you can lay your hands on.’ In the end, we had sixteen private helicopters, and we had about eight army helicopters.

Q: How did you design the lineup of artists that would appear?

John Morris: We tried to break the show up into three days. A softer beginning day, we had the folk artists, Joanie Baez, Ravi Shankar and Tim Hardin. The second day was to be more English East Coast (The Who, Janis Joplin) and the third day was more California groups (Crosby, Still, Nash and Young, Jimi Hendrix). We went after the best people there were.

Q: Michael, why was it called ‘Woodstock?’

Michael Wadleigh: The reason they were calling it Woodstock was because for 200 years this great little village of Woodstock, in upstate New York, had a long history of radicalism. They wanted to do a festival that mirrored the counterculture, anti-establishment, left-wing point of the village. I thought it was a great idea, because it would not just be music, but it would be social consciousness.

Q: Michael, on a daily basis how did you know what to shoot?

Michael Wadleigh: We had basically two tasks, the peace part of it and the music part of it. For the music, our idea was to photograph only the songs that had lyrical content that related to the ideas of the Sixties, the Woodstock generation. We always had these ideas of the multiple images, so we had the cameramen stationed around the stage, and we would give them rough assignments as to which people they would cover in the band. In terms of the documentary, our idea was to cover what seemed really important, from people sleeping to getting up and washing and bathing, to eating, the toilets, calling home, the reaction of the town’s people, the nude bathing, the drugs.

Q: On Sunday, that infamous storm relentlessly hit the area. How did you cope?

John Morris: It was listed, in fact, as a tornado. We had a 50-mile-an-hour wind come shooting in from what would be the right field line.

Michael Wadleigh: If it had come through straight on, God knows how many people would have been wiped out. And I don’t think any of us would have ever recovered if there had been a death like that.

I’ve been in a number war zones and it’s not that I’m personally brave, I just think it isn’t built into me to think that it’s my time.

Q: John, Joe Cocker, who was performing when the storm hit, was asked to leave the stage. I believe you were left to control the crowd.

John Morris: I had just been told that Joan (Baez) was having a miscarriage, that my wife had fallen and had broken her ankle, my dog had disappeared and somebody in the audience had a gun!

Michael climbed up on the stage and was down on one knee [filming] and here I was with this mic that was shorting into my hand. It is as close to a nervous breakdown that I’ve ever come in my life.

Q: John, you got to introduce the last act of Woodstock, Jimi Hendrix and then, I heard, left the stage to take a nap in your trailer.

John Morris: When Hendrix hit the ‘Star Spangled Banner,’ it woke me up. It surprised the hell out of everybody. It was just unbelievable. I looked out of the window and there were only about 30,000 people left. It was Monday morning around 6 a.m.

Michael Wadleigh: Probably the most famous piece of political rock and roll is Hendrix’s Woodstock Star Spangled Banner where he does it with the bombs, the sirens, the people screaming and dying in the streets. It’s an incredible version. It’s been used by everyone from the Rolling Stones to Guns ‘n’ Roses and U2 to close their shows.

Q: Michael, with all the footage you had, how did you decide what to use?

Michael Wadleigh: We looked at every bit of it in a very methodical fashion. My partner in this was Thelma Schoonmaker, a renowned editor. I think the first cut was seven hours long, and then we just started cutting it down from there.

Q: The ad for “Woodstock” stated, ‘No one who was there will ever by the same.’

Michael Wadleigh: You almost mark your life by whether you were or were not at Woodstock. If you were, it made an indelible impression upon you for the rest of your life.

John Morris: Margaret Mead, of all people, called it one of the most important sociological events of the 20th Century. If you were there it had to change you.

Note: Both Thelma Schoonmaker and Martin Scorsese worked on the editing team for “Woodstock.” She was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Editing for the documentary, and later won three Oscars for “Raging Bull,” “The Aviator, and “The Departed,” all directed by Scorsese.

Portions of this article were first published in Film Review Magazine