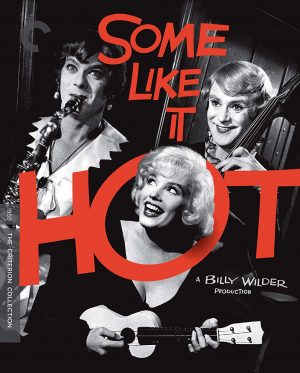

This interview is the first of a series of vintage interviews with beloved Hollywood celebrities reflecting on their most famous films. All of the interviews were conducted by veteran Hollywood correspondent Judy Sloane, who is now a regular contributor to Frontrowfeatures.com. We hope you enjoy taking a walk down memory lane with Judy and the various celebrities (most of whom have long since passed) talking frankly and openly about the films that made them famous. This first installment is an interview with the late great Jack Lemmon, who famously co-starred with Tony Curtis and Marilyn Monroe in the 1959 Billy Wilder-directed comedy “Some Like It Hot.”

By JUDY SLOANE

Special to Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Based on the 1951 German movie “Fanfaren der Liebe,” Billy Wilder’s comedy “Some Like It Hot,” was released on March 19, 1959, and became an almost overnight classic.

Set in 1929, the film told the story of two unemployed musicians, Joe (Tony Curtis) and Jerry (Jack Lemmon) who not only witness the St. Valentine’s Day massacre, but are seen by the gangsters. Running for their lives, they disguise themselves as women; respectively Josephine and Daphne, to join Sweet Sue’s all female band featuring vocalist, Sugar Kane (Marilyn Monroe).

In 1993, I spoke with Lemmon, who was nominated for an Academy Award eight times, winning twice, about his iconic role in this comedic masterpiece, considered one of the best films ever made.

Judy Sloane: How did you first hear about “Some Like It Hot?”

Jack Lemmon: It had been going on, but I hadn’t heard about it, and other people were being discussed. God, from what I’m told, everybody from Frank Sinatra to Danny Kaye were up for the part (of Jerry/Daphne.) One night, I was in a little restaurant called Dominick’s and Billy Wilder was there. As I passed his table, Billy said, “Do me a favor, on your way out would you pop by? I’d like to speak with you for a minute about a script.” I said, “Of course.”

So, I sat down and Billy gave me a capsule version of the script, saying, “It’s about two musicians that witness the St. Valentine’s Day massacre and, in order to save their necks—because they are also seen by the gangsters—they have to join an all-girl orchestra. Needless to say, this is no heavy drama. If you want to do it, you’re going to be in drag for 85 to 90 percent of the film. Do you want to do it?” I immediately said yes.

Sloane: Were you apprehensive about dressing in drag? It was the fifties, and it wasn’t done as much at that time.

Lemmon: Yeah, there was mild apprehension only, because it was Billy Wilder. With anyone else, I would have said, “I’d like to read it first and see what my reaction is.” I immediately said yes because I had great respect for Billy and his work, and I figured there’s no way it’s going to be distasteful.

Sloane: When you first read the script did it read as funny as it played when you got it on its feet?

Lemmon: Yeah, I think it’s the greatest comedy script I’ve ever read.

Sloane: Were you concerned that the combination of gangsters, killing and the comedy might not mix well together, because I know the studio was worried about that?

Lemmon: No, I wasn’t. Billy was concerned but not worried. It was one of the reasons why he wanted to do it in black and white and not color. He didn’t think it was going to be palatable if you had red blood on the screen in a comedy.

Sloane: What was your first reaction when you and Tony Curtis put on women’s clothing?

Lemmon: When we first put it on nothing seemed to work, because the costumes and the wig didn’t seem to go with the make-up. So for about four or five days in a row, Tony and I went into Goldwyn Studios and we worked with our two make-up men and then finally I unconsciously started imitating some of the things that I saw in my mother, and then I exaggerated them.

Finally, we got the wigs the way we liked them, and then either Tony or I—he says it was my suggestion, I thought it was his—said, “Come with me. Here’s how we are going to find out how this works.” And we walked down the street on the Goldwyn lot, all decked up as the girls in the band, and went into the ladies room at the commissary. Just futzed around in the outer room there putting more lipstick on and using falsetto voices, and going, “Oh, hi honey,” to the other girls, and not one of them batted an eyeball. They thought we were in some period picture there. They totally accepted us.

We (then) went to Billy’s office, and he looked and said, “Hello, girls.” I told him what we just did, and I said, “Not one girl batted an eyeball.” He said, “Don’t touch anything.”

Sloane: Didn’t Marilyn Monroe end up wearing one of your dresses?

Lemmon: Yeah, she stole my dress. (He laughs.) It’s the only time I’ve ever had any of my wardrobe stolen by a star. It was about 48 hours before we started shooting (and) she saw my black dress hanging up there and said, “Oh, I love that.” And Orry-Kelly—he was the designer and a brilliant one—whipped something up really quick for me. (I think) it was pink.

Sloane: You and Tony had a great onscreen rapport. Was that there from the beginning or did it grow as you worked together?

Lemmon: It grew. I mean, we had a good rapport, but it definitely grew as we went on. No question about that.

Sloane: I read a wonderful article by I.A.L. Diamond (who wrote the screenplay with Billy Wilder) that said that even when Marilyn took 47 takes to do one line like, “Where’s the bourbon?” neither you nor Tony Curtis every complained. What was it that gave you that kind of patience?

Lemmon: Well, if you start complaining, is that going to make her say the line right? No. Because she was trying, she really was. What happened is Marilyn had a built-in alarm clock and the only way she knew how to work was when it felt a certain way, which was right for her.

So, she would stop the takes, not Billy, and it wouldn’t be because she blew the line. It would just be that something was wrong with the take or with her in the take, as far as she was concerned. She’d say, “Sorry,” and start shaking her hands and she’d walk outside the door again and get back on her spot to start. I think Tony lost $15, or I did. One of us bet that we’d go 50-something takes, and the other said, “No, she’ll get it by 40.” And we went 50-something takes, as I remember. It was an enormous amount of takes for seven words. “Where’s that bourbon? Oh, there it is.”

Sloane: Did the fact that you had to be great in every take become an overwhelming pressure, because the one that Marilyn got right would be the one that was used?

Lemmon: Yeah, there was a certain pressure with that because there’s no question that that would enter into it. After a while, she got it right and that’s going to be the print. So you’d better be there.

I’ll never forget, I was stunned one morning. I walked on the set to one of my favorite scenes, and one of the best scenes I think in the train sequence. I’m in the upper bunk and Marilyn jumps in bed with me, and she’s talking away and I’m answering. The lines are marvelous. We rehearsed it once and she was damned near letter-perfect, and Billy said, “Let’s try one.” We did it, Billy said, “Cut, was that good for camera?” The cameraman said yes, and Billy said, “Print.” It was take one.

Sloane: Did you have as much fun playing Daphne as it looked like you were from the audience’s perspective?

Lemmon: Yeah, especially as the film went on and I realized how wonderful this thing could be.

Sloane: You were nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor for your role. What do you remember about that awards show? Did you think you were going to win?

Lemmon: No, I knew that the chances were very, very slim, especially since when I was a kid I won (playing) Ensign Pulver (for “Mister Roberts” in 1955). That was supporting, but the old Hollywood superstition was if you win it in supporting you will never win the other one. Eventually, I was lucky enough to be the first one to receive both of them (He won Best Actor for “Save the Tiger” in 1973.)

Sloane: Did you ever have an inkling when you were making this movie that you were making cinematic history?

Lemmon: No, I thought we had a chance to do something really terrific.

Portions of this interview were first published in Film Review Magazine.