By ANGELA DAWSON

Front Row Features

Filmmaker John Scheinfeld reveals that his scope of knowledge about jazz icon John Coltrane was limited when he began his journey to document his life a few years ago.

“Like many people, I was introduced to his music through his recording of ‘My Favorite Things,’ which was a big AM radio hit for him in the 1960s,” recalls the Chicago native by phone. “When I was asked if I was interested in making a film about John Coltrane, I said, ‘Let me go do a bit of research,’ and the more I read about his story, the more I became convinced that this was something special.”

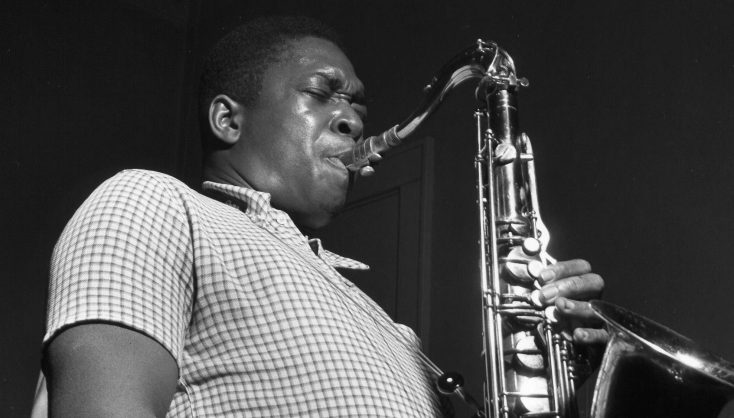

That “specialness” was the atypical trajectory of the skilled saxophonist’s remarkable yet all-to-brief life and career. Coltrane, simply known as Trane to fans and friends, died at age 40 of liver cancer, yet he left behind an incredible body of work. Everyone’s seen the story of a young artist with great talent coming from nowhere, who hits it big and makes a lot of money, stars abusing substances and then dies young. Scheinfeld’s documentary, “Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary,” chronicles the life, the career, the spirituality and the impact of one of the world’s legendary jazz musicians.

“Coltrane was the antithesis of that,” remarks the filmmaker, who previously has made documentaries on iconoclast artists including John Lennon (“The U.S. vs. John Lennon”), Harry Nilsson (“Who is Harry Nilsson (And Why is Everyone Talkin’ About Him?”), Rosemary Clooney “Rosemary Clooney: Girl Singer—Songs From the Classic Television Series,” as well as stars in other fields.

Coltrane abused alcohol and drugs (mostly heroin) early in his career, and that dependency nearly snuffed out his fledgling career when he was kicked out of Miles Davis’ quartet for showing up high to gigs again and again. As Scheinfeld’s documentary reveals, it was only after the North Carolina-born saxophone player and composer cleaned up his act (by going cold turkey) in the early 1950s that he really began to develop as an artist.

“He had challenges early on in his career but it was when he overcame those challenges, when he overcame his addictions, that he ascended and became the iconic figure that he became and that we know today,” Scheinfeld says.

Viewers who appreciate the power of music to entertain, inspire and transform are likely to enjoy this smart, passionate, thought-provoking and uplifting documentary. The film, created over 18 months, is produced with the full participation of Coltrane’s family and the support of the record labels that collectively own the jazz artist’s catalog. Set against the social, political and cultural landscape of the 1950s and 1960s, “Chasing Trane” brings Coltrane to life as a fully dimensional being, inviting the audience to engage with Coltrane the man and the artist. Oscar winner Denzel Washington (“Glory,” “Training Day”) provides the voice of Coltrane, derived from interviews.

“Chasing Trane” features never-before-seen Coltrane family home movies, footage of saxophonist and his band in the studio (discovered in a California garage during production of the film), along with hundreds of never-before-seen photos and rare television appearances from around the world. The story is told by the musicians that worked with him (Sonny Rollins, McCoy Tyner, Benny Golson, Jimmy Heath, Reggie Workman), musicians that have been inspired by his groundbreaking music and creative vision (rapper Common, The Doors’ John Densmore, jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, guitarist Carlos Santana, and jazz saxophonists Wayne Shorter and Kamasi Washington), Coltrane’s children and biographers and by well-known admirers such as President Bill Clinton and philosopher Dr. Cornel West.

Q: There are challenges in making any documentary. What were the challenges of this one?

Scheinfeld: Every documentary I’ve done has its own peculiar challenges. Usually, they revolve around what tools do you have to adequately tell a dramatic, emotional and compelling story. I did a film a few years ago called “The U.S. vs. John Lennon” and Lennon was one of the most photographed and filmed personalities of the 20th century, so material was not an issue. I did another film called “Who is Harry Nilsson and Why is Everybody Talking About Him.” Harry never did any concerts and only did a handful of TV shows so that was quite a challenge to come up with enough audio-visual material to tell his story. Coltrane is somewhere in-between. He did a number of television concerts in Europe and we had access to those. He was photographed quite a lot. I’m very proud of our team. We feature probably 500 photographs in this film that have never been seen by anyone, except the photographer that shot them. We were able to use shots from their contact sheets and their negatives that had never before been developed and shown. So that was one particular challenge: the audio-visual material. There wasn’t a lot of performance but there was enough.

One of the biggest challenges was, though, in his lifetime, Coltrane didn’t do any television interviews and only did a handful of radio interviews, and the sound wasn’t good enough on them for me to use, but I wanted him to have a very vital and vibrant presence in the film beyond just the performance clips. Fortunately, he’d done a lot of magazine and newspaper interviews at the height of his career, so I took extracts from those interviews and peppered them throughout the film to illuminate what he might have been thinking or feeling at that particular time in his life. The advantage to do that was that we could now bring John Coltrane alive as a three-dimensional human being. Without his own words, I think we would have had a challenge that we couldn’t overcome.

One of my goals in making “Chasing Trane,” was to make him into a fully dimensional human being, not just the serious, thoughtful artist you see on the record covers. Then the task became, who speaks those words? Because I am relentlessly optimistic and I aim high, I felt I wanted to get a movie star to read them. I put together a list of five actors I felt would be right for this and I went to a casting director friend of mine, (Victoria) Thomas. I didn’t know it at the time but she was (casting) “Fences” for Denzel Washington. I asked to help me with this and she said, “Sure.” She asked me to write me a description of my vision for the film and what I wanted the actor to do and she promised to send out the request. Three days later, I received a text from her that read, “Denzel’s in and he needs to talk to you.” She gave me his phone number so I called him and he picked up. He told me was intrigued by the idea of a documentary on Coltrane, but he wanted to see a rough cut of the film first, so we sent him that. Five days later, he called me and said, “It’s beautiful, brother! When are you coming to Pittsburgh?” because he was there filming “Fences.”

We went and on one of his free days and recorded him. I’ve worked with a number of celebrities, some of whom don’t bother to look at the script before they get in the studio, but Denzel had really prepared. He knew how he wanted to “play” Coltrane. He didn’t mimic Coltrane; not many people know how Coltrane spoke, so it’s an interpretation, much as he would have done had this been a scripted biopic.

With any music documentary, one of the biggest challenges always is clearing music (to include in the film). Fortunately, we made an arrangement with the Coltrane family. We had their full support and participation. They control all of his compositions. We also made an arrangement with the record label that collectively owns about 95 percent of Coltrane’s catalog. As a result, we’re able to feature 48 Coltrane recordings in this film, which is a lot for any documentary. I think it really helps tell his story in the most compelling way.

Q: Is there any crossover between any of the artists that you’ve profiled in your documentaries?

Scheinfeld: No, but the common thread for me is that these are all artists that went their own way; they found success on their own terms. They followed their muse and their art wherever it took them, irrespective of commercial concerns, critics and even the audience. I find that very admirable about an artist; they follow their path. And Coltrane was very much like that. Like Lennon and Brian Wilson, even, and the Beatles, each album that Coltrane did was different from the one that came before. He was constantly pushing the envelope, constantly experimenting with this sound, constantly growing and evolving as an artist, a composer and a player, and I think all the great artists have that in common. They don’t sit still. They don’t repeat themselves. They’re on a journey to keep growing. Many of the people I’ve done docs on share that in common with Coltrane.

Q: It was interesting that you found a photo of his band mate, double bassist Art Davis, with a camera, and then went to his estate and sought out footage that he shot of Coltrane.

Scheinfeld: I call that treasure hunting. That’s always the most fun of the documentaries that I’ve done, which is looking for the rarest, the most unusual and the unseen material. We were at the home of Chuck Stewart, who recently passed away, but he had been a world-class photographer. He’d shot many celebrities and musicians over his career. And shot Coltrane more than any other photographer. We were at his house. I didn’t want simply the shots that showed up on album covers; I wanted to see contact sheets and his negatives. He was very cooperative and brought out a whole stack of things. At some point, while going through the stack, I said, “Oh my God!” And it was Art Davis in the studio with Coltrane, and I said, “Look what he’s holding in his hand.” It was a super 8 movie camera, so I’m thinking he shot the session. While there were many photographs of Coltrane in the studio, there was no known footage. Our researcher, Kiku (Lani Iwata), found out that Art, who had passed away, had a son who lived in Van Nuys, Calif., and we called him up and explained to him what we were looking for, and he said, “Oh yeah, I’ve got all the home movies in the garage.”

We went over there over several Saturdays and looked at them. Many of them were the usual home movies but then we found a 7-1/2-minute color roll of film shot in the studio by Art, and never seen (publicly) and very graciously they allowed us to use pieces of it in “Chasing Trane.” And there were a number of others things. One of the biggest finds is when we came to Japan to do some shooting for the film, and we met an artist who came into possession of a scrapbook with 300 photos taken during Coltrane’s last tour, which was in Japan. This young photographer was given access and there are many intimate shots behind the scenes, on the train, on the plane and at the hotel. He died in 1970. The scrapbook found its way to this English teacher who put it in the closet for 40 years. When she passed away, into the possession of this artist, who was more than happy to let us use them.

I love the detective work and this film is no exception. People who come to see the film will see many images that no one, outside of the people who made, them, have ever seen before.

Q: You interview a number of colleagues, music artists and celebrities in this, including President Bill Clinton. How easy or difficult was it to get them to participate?

Scheinfeld: It wasn’t difficult. When I decide who I’m going to interview in a film I “cast” them much like one would approach a scripted feature, meaning I want people with unique voices, with different perspectives, who look and sound different, and aren’t making the same points. For “Chasing Trane,” they were divided into four parts. The first part were people that knew Coltrane and who could speak with legitimacy and credibility to who he was as a person and as an artist. That’s why we have jazz legends like Sonny Rollins, Benny Golson, Jimmy Heath, Wayne Shorter.

Then I wanted family members so we interviewed three of his children with the love of his life, Alice Coltrane, and then we interviewed Antonia Andrews, who is the stepdaughter from his first marriage. I’m so delighted with that because in her entire life, she’d never given an interview. It took months to persuade her but she finally did it and she’s wonderful in the film. It allows us an intimate window into Coltrane, the father and Coltrane, the person.

I also wanted some people who are artists of note in their own right who had been influenced by Coltrane. That’s why we have Carlos Santana, John Densmore, Common and Kamasi Washington. They speak to the reach and the power of Coltrane’s music and how it has affected their own creative work.

And I always like to have unexpected choices. In this one, it was (philosopher) Cornel West, who has such a wonderful and elegant way of speaking. Sometimes your smart, and sometimes you’re lucky. Well, I was lucky on this one because, initially, I wanted him to talk about the black experience since Coltrane grew up in the Jim Crow south in the 1950s. When I sat down to talk to Cornel, imagine my delight that he is an obsessed Coltrane fan. He knew events from Coltrane’s life so he could connect those to the black experience in a very meaningful and important way. The other one was Bill Clinton. We’ve all seen images of him playing the saxophone. He tells the story of how he picked up the sax at age 10 and played it all the way through high school. He says that when he was looking at colleges, he actually got more scholarship offers for his musicianship than his academics, and he seriously thought about becoming a professional musician, but he realized he was no John Coltrane. I figured there was a story there so I reached out to his team. What came back was, “We think the President would find much joy in doing this interview,” and then it took us 10 months to get him. His schedule is so busy and, of course, he was on the campaign trail for his wife (Hillary). But one Friday afternoon, I got a call from his team that told me to come to New York, so I flew from Los Angeles and got him.

Getting these people wasn’t so hard as scheduling them. They’re all working artists and have very busy schedules. Finding time where they actually could sit down was the biggest issue. All of them had such passion for Coltrane that getting them to say yes was relatively easy.

Q: It took you 18 months to make this film. Who was the hardest interview to get?

Scheinfeld: We could have been done sooner but we were waiting for Denzel, the President and Wynton Marsalis. We were honored to be selected by the Telluride Film Festival for the World Premiere and the Toronto International Film Festival for the International Premiere, but I had always had my eyes set on a theatrical release in the U.S. Happily, the critical response has been great. We’re delighted to be working with Abramorama. As of a few days ago, we’re on 83 screens, and growing every day. I’m just thrilled as a kid from the Midwest to have something I made be in movie theaters is a great dream and we’re living the dream at the moment.

Q: Do you think this film will appeal to an audience beyond jazz fans or Coltrane fans?

Scheinfeld: I didn’t want to make a film just for Coltrane fans, or just for jazz fans. The word “jazz” only appears in the film around four times. It’s really a portrait of an artist. Anyone who appreciates great art and is interested to know the forces that impacted on the artist, that shaped him or her as an individual and as the artist, will find this story really interesting.

Again, what I think distinguishes Coltrane from many artists from whatever genre of music you’re talking about, he really was on a spiritual journey. This is a journey film. It’s showing how he grew and evolved and all the interesting things that happened to him along the way. That’s what fascinated me and that’s what I hope (“Chasing Trane’s”) viewers will find fascinating as well.