By JUDY SLOANE

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Ken Burns’ new documentary, “Benjamin Franklin,” spotlights one of the most consequential figures in American history. Statesman, scientist, inventor, writer and publisher, this Founding Father signed both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.

His 84 years spanned practically the entire 18th century, but Burns, a genius in crafting this form, covers Franklin’s life in two parts, airing on PBS April 4 and 5, 8-10 p.m. ET (check local listings).

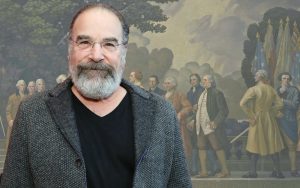

At the TV Critics virtual tour, Ken Burns was joined by Walter Isaacson, the author of “Benjamin Franklin: An American Life” and actor Mandy Patinkin, who voices Franklin in the documentary.

Q: Benjamin Franklin seems to be one of the few right‑brain/left‑brain people. He was a legitimate writer in one sense, but he also was a scientist and inventor.

Walter Isaacson: The importance of Ben Franklin is that he was able to connect art and science, the humanities and the technology. He cared about everything you could possibly learn about anything, from art to anatomy, to math, to music to diplomacy.

Q: What about his writings?

Isaacson: (Franklin) invents a classic form of American writing. He’s the first to do it. It is a casual, aw-shucks, cracker‑barrel‑type humor in which he’s talking in an informal way, whether it is “Poor Richard’s Almanack” or any of the parodies and hoaxes that he writes for his newspaper or autobiography. “His” form of humor leads you to Mark Twain and Will Rogers and so many others, and it pokes fun at the pretensions of the elite.

Q: Whenever we see Benjamin Franklin in films or plays, he’s always this go-to guy. The other American leaders would go to him for advice. Was he really like that?

Isaacson: If you have a team that’s putting something together, you need different talents. With the founders you have George Washington, who is a person of high rectitude. You have to have smart people—like Jefferson and Madison—and passionate people—like John Adams and his cousin, Samuel. But what you really need is a wise person who can be the go-to person who people come to, that was clearly Benjamin Franklin. He had a system whereby you listen. You always ask Socratic questions, and then you try to find a balanced and wise solution.

Q: Ken, what made Mandy Patinkin the perfect actor to embody the voice of Benjamin Franklin?

Ken Burns: There was an epiphany that I had very early on in this production, that there could be only one person who would read the voice of Franklin, and that was Mandy, who I have adored and respected for a long time. One of the great benefits in my life is not only to have Mandy say yes, but also to have him work so unusually to hone-in and find this voice, and to inhabit every single word.

Q: Mandy, when you’re speaking the actual words of a person and not a fictionalized script, do you treat it like any other performance or a reading?

Mandy Patinkin: I look for the connective tissue so that I can connect to it, whether it’s my image or voice or both together. That’s what makes me alive. That’s my job, to be alive in front of the camera or the microphone and inhabit (Burns’) wishes.

Q: Would Benjamin Franklin be an interesting character to play in a movie?

Patinkin: Oh, my God. I consider getting to be his voice for those sessions one of the privileges of my artistic life. I really just focused and learned that some of it almost sounds like a foreign language at times, but I wanted to understand what was being said (and) what were the ideas at hand.

I heard that Michael Douglas is getting to play Benjamin Franklin in a film. I have never been jealous of any of my fellow actors my whole life. I love Michael Douglas, and I’m completely jealous that he’s getting this opportunity.

Q: The documentary covers the Constitution which (initially) stated every person who was not free was three‑fifths of a human being. Can you talk about that?

Isaacson: I think the three‑fifths clause was a very complex compromise. It was done because they didn’t want the South to be able to have all the enslaved people count in the population.

Treating Blacks as three‑fifths of a person was an odious compromise. Whether it was done to help the South get representation or hurt the South, it was dehumanizing.

They got it wrong, and Franklin knew it, which is why he dedicated the rest of his life after the Constitutional Convention to being an abolitionist, to decrying the notion of slavery, and trying to get rid of it.

Q: Ken, is this documentary in some way different from others that you’ve made? It highlights the situation with regard to enslaved people, women’s rights and Native Americans. Would some of this not be emphasized to this degree if it has been made 10 years ago?

Burns: I think probably you’re right in some respects. Obviously you make the film in whatever present moment you’re in. But I would refer you to (my) films on the Statue of Liberty from the mid‑’80s, the Civil War, baseball, jazz or the National Parks that included both race and indigenous people questions. That has been part of our bailiwick.

This is the central question of the United States. It comes from the three‑fifths (clause). It comes from the fact of the Declaration (of Independence) was written by a guy who said, “We hold these truths to be self‑evident, that all men are created equal,)” (who) owned hundreds of human beings in his lifetime and didn’t see the hypocrisy and the contradiction. So this has been part of what we’ve always done.

Just as we grow up and mature, I hope, and get better as filmmakers, we learn subtler and more specific ways to address and engage it.

Patinkin: Can I just add one thing to your beautiful words, Ken? As storytellers, I feel we are obligated, to echo William Shakespeare’s words, continually to “hold that mirror up to nature”—and he wasn’t talking about trees, he was talking about human nature.

Forgive me historians if I get the numbers wrong, but I think we had 250 Founding Fathers out of 250,000 people. Now there are over 300 million people. Where are those 250 (today)? I’ll take 20. Where are they?

Watch this film and encourage your friends, relatives, young people (and) children to come out of the woodwork. We need you. The world needs you.