Note to editor: Brand uses the phrase “cocks and balls” and the word “tits” in one of his answers (all within the same paragraph).

By JAMES DAWSON

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Dressed like a vested hippie biker adorned in necklaces, bracelets and tattoos, the hyper-animated Russell Brand comes on like a one-man show promoting his new movie “What About Dick?” Brand has the title role in the campily absurd comedy as an early-20th-century Englishman of “ambivalent sexuality” whose name is the source of numerous naughty double entendres.

Although written and co-directed by Monty Python’s Eric Idle, who co-stars with Brand and other British comedy royalty including Eddie Izzard, Tracey Ullman, Billy Connolly, Tim Curry, Jane Leeves, Jim Piddock and the literally royal Sophie Winkleman (a.k.a. Lady Frederick Windsor), the movie will not appear in theaters or (for the time being) on DVD. Instead, it will be available exclusively online for download beginning November 13 (at whataboutdick.com).

The movie marks a new accomplishment for actor/singer/writer/interviewer Brand, whose onscreen roles have ranged from debauched rock star Aldous Snow (In both “Forgetting Sarah Marshall” and “Get Him to the Greek”) to Shakespeare’s Trinculo (in director Julie Taymor’s version of “The Tempest”). “What About Dick?” is a retro staged reading before a live audience. The actors stand behind microphones to do their parts, a live band accompanies several songs and an on-stage crewmember provides sound effects. It’s all quite silly, with a few ad-libs by the cast.

Although given his own solo interview slot at the movie’s Hollywood press junket, Brand couldn’t resist crashing an earlier group interview that featured Idle, Connolly, Curry and Winkleman. Brand’s lengthy stream-of-consciousness comments were delivered at roughly twice the speed of normal human speech and with almost messianic zeal.

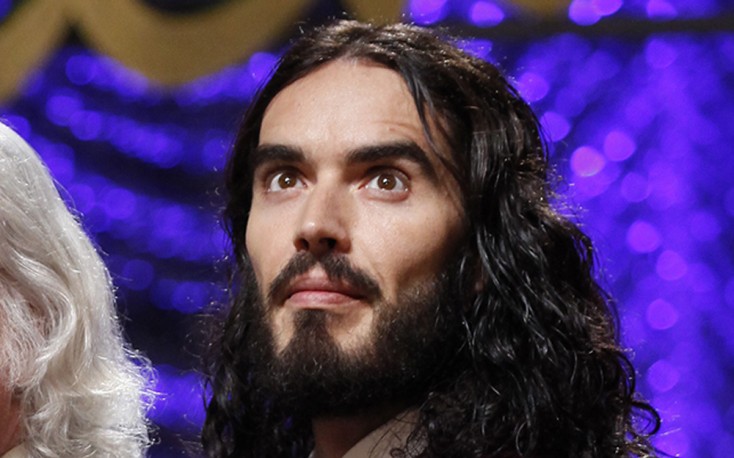

Black-bearded and with matching past-the-shoulders wavy hair, the dark-vested Brand arrives eating an apple and carrying a paperback of Steve Martin’s tweets.

Brand: I like roundtables, because it makes me feel like I’m important. Why do you think I have to be on my own? Why do you think that? That’s my question!

Q: Where does your sense of humor come from?

Brand: I think the original sense is inherent, but you have to cultivate it and educate it. Like some people would be good at football or basketball or something, but then they require the training, don’t they? So what I think it comes from—and I think this must be true, because every time I think about it, it’s a pang for me that nearly makes me cry—that it’s a response to pain and fear. It’s a response to the knowledge of death. It’s a response to the certainty that there’s something else, that humor provides us a moment of respite, relief. An explosion away from the conformity, the unnatural condition we’re forced to live in as these gentle animals that we are. These beautiful, angelic simian creatures forced into conformity, stripped of our dignity, robbed of our spirituality. Everything we ever were repackaged back to us at a price, commodified cellular slavery. And I think the humor temporarily alleviates that burden, it shows us that our spirit lives on, that we can change things, that we can triumph against all adversity.

And an important thing that the Maharishi said: “Life is not serious. Life is absolutely not serious.” There’s always a march stolen by the intellectual elite, by the atheists, that somehow we have to be grown up, that somehow we have to be serious. That there’s some obligation towards academia and bureaucracy. But the fact is, we can just be silly if we like.

Q: Does comedy give you the license to cross lines? In the movie, the audience’s reaction seemed to inspire you to go farther and farther, such as when you were nursing at Tracey’s breast. You wouldn’t do that in someone’s living room or at a dinner party.

Brand: No, indeed not. That’s what’s beautiful about live performances. You’re offered that opportunity to enter in a discourse with the audience. They’re so important. Performers are generally such fragile creatures that if you laugh, it feeds you, you become inflated, you recognize that connection. It’s a kind of circuitry, isn’t it? An invisible circuitry. If you imagine neurologically what occurs in the mind of each of us, there are synapses, the synapses fire electromagnetic energy across a space creating a circuit, and that circuit will become a thought or an action. I think that this circuitry can exist between individuals as well. That unseen between us there are connections. And I think that if, in an audience, you have that energy, that laughter, then you are connected and the thing can flourish and grow.

Q: As an actor, what kind of preparation did you have to do to play a Dick?

Brand: You’re being cheeky, ain’t you? You’re being cheeky. What preparation did playing a Dick require? A lifetime of rehearsal.

Q: How many of the cast members did you know beforehand?

Brand: I knew only Sophie Winkleman of the cast, prior to working on this. (Brand then delivers a joking, extended and completely deadpan dismissal of Winkleman’s contribution to the film.) And for me she stands alone as a blemish on an otherwise perfect portrait. But for her involvement, we could have achieved comedy greatness. This could have gone down in the annals as a great work of genius. But Sophie Winkleman (was) a single tear in the canvas of perfection, like on an Arabian rug, as not to offend Allah, one error is always included. Sophie Winkleman is that Arabian error. Have you noticed, as I have, how minute her eyes are? Such narrow, tiny slits within a face, barely a soul peeping through, just further nothingness.

Everyone else I hadn’t met before. Eric I only knew from his great work on “Monty Python.” Eddie I knew from being devoted to his standup comedy. The same is true of Billy and Tracey.

I just took it as some kind of comedy school, to tell you the truth. For me, it was like an education. I went there just to learn.

Q: Eric talked about the response of the audience to women being funny. He felt that it makes especially men feel uncomfortable. Has that been your experience?

Brand: When women are funny I like it, but let’s think about that for a while. In a patriarchal culture, women behaving humorously. What is humor? I mean, we talked about the role of comedy a little bit before, didn’t we? I suppose that we don’t like women being funny because of how they’re the archetype of the mother and the archetype of the lover. Neither of those things…you want stability in both of those things. We see women in opposition to the patriarchal self, don’t we? So if they start being funny and disruptive, it’s scary.

Also, on a more basic physiological level, men have got, like, cocks and balls, stupid looking things, not inverted elegant genitalia. I think that there’s always some emblem in anatomy for psychology. I think the consciousness of the body is more important than people acknowledge. Although tits are pretty funny, aren’t they?

Q: Do you ever see yourself doing something on a blockbuster, big-budget scale? A new “Star Wars” is coming out…

Brand: (In mock surprise) What?

Q: Yeah, they’re coming out with “Star Wars” VII, VIII and IX.

Brand: (Indignantly) Why wasn’t I invited to play Darth Vader?

Q: I can see you as a Jedi.

Brand: I could be a Jedi! Those f****** slags! Why have they not invited me in to participate?

Q: Would you do it?

Brand: Yeah! Anything like that, aye. Anything like that, to be a Jedi for the children. As yet unborn.

Q: It is true that within the heart of every comic is a serious actor wanting to get out, such as when Robin Williams got accolades for “Good Will Hunting?”

Brand: Well, I’ll tell you what that is. It’s because of the enormous sensitivity required to be a comedian. So, like Robin Williams, there’s a velocity of thought. Comedy and tragedy obviously have a relationship with each other, so you have to inherently understand what the tragedy is to play the comedy. That’s why there’s so much value in dark humor. Because the darker, the more upsetting, the more indiscreet, the more macabre and painful the subject, the more fertile comedically it becomes, in my opinion. So it doesn’t surprise me that comedians can become very good actors. It surprises me that so many choose to.

Q: What made you want to be vegetarian?

Brand: Morrissey said, “I don’t see why something’s life should end just so I can have a snack.” Bad to kill a thing.

Q: You’ve played musicians as Aldous Snow and in “Rock of Ages.” Would you like to do a musical on Broadway?

Brand: Yeah, I want to be Fagin, in “Oliver!”