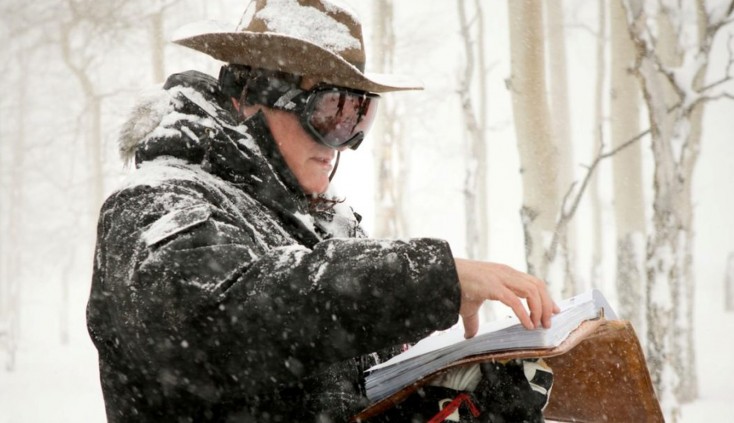

Writer/Director Quentin Tarantino (l) on the set of THE HATEFUL EIGHT. ©The Weintein Company. CR: Andrew Cooper.

By ANGELA DAWSON

Front Row Features

HOLLYWOOD—Self-described film buff Quentin Tarantino shot his new wildly over-the-top Western “The Hateful Eight” in the mostly disused “Ultra Panavision” 70mm format.

The film, starring actors who regularly appear in the filmmaker’s repertory including Samuel L. Jackson, Tim Roth and Michael Madsen, along with newcomers to Tarantino world such as Jennifer Jason Leigh, Kurt Russell and Channing Tatum, is now in theaters in a 167-minute wide-release version as well as an 187-minute “roadshow experience” that includes an exclusive overture and a 12-minute intermission.

The outspoken Tarantino, who has gotten into hot water recently with American police departments over comments about the rash of officer-involved shootings involving black suspects, once again defended his remarks at a recent press event as well as discussed the technical and creative choices he made with his latest film.

Q: Regarding your use of Ultra Panavision, obviously, it’s epic in scale in terms of what you use in the frame but can you to talk about what it gives your actors in terms of intimacy, in terms of the close-ups, in terms of the relationship of one actor to the other and what that means to you as a filmmaker to be able to shoot actors in 70mm?

Tarantino: You actually kind of answered your own question because literally that is one of the tricks that I thought about was the intimacy that it provides you in between close-ups. I shot a lot of close-ups of (Samuel L. Jackson) but I’ve never shot them as beautiful as I did in this movie. You find yourself taking backstrokes in his eyes. It’s just the way it is.

But one of the things that I remember when I did the film—when it was reported that I was going to do it in this format—people were actually speculating, “Well yeah, okay. That sounds really great but why would he do it for a thing that’s just so set back?” I think that’s actually just kind of not very profound thinking when it comes to 65mm—that it is basically just for shooting travelogues, mountain sceneries, nature and stuff.

I actually felt that especially in bringing it into Minnie’s Haberdashery (where much of the action is set), if the film isn’t suspenseful, i.e., the pressure cooker situation of what’s going on in the movie, if that’s not part of it, if the threat of violence and the temperature isn’t always getting up a notch every scene or so, then the movie is going to be boring. It’s not going to work. I actually felt that with the big format, one it would put you in Minnie’s Haberdashery. You are in that place; you are amongst those characters. I thought it would make it more intimate when I got in close with them. But the other thing that I thought would be very very important is there are always two plays going on in this movie, once you’re in Minnie’s in particular.

There are the characters that are in the foreground of any given scene and then there are the characters in the background. You always have to be keeping track, especially in this scenario of where everybody is. It’s like they’re pieces on a chessboard and you always have to see it. So, maybe it might be Chris Mannix (played by “Justified’s” Walton Goggins) and General Smithers (Bruce Dern) who are dealing, but you’re also clocking Joe Gage (Madsen) at his table and you’re clocking John Ruth (Russell) and Daisy (Leigh) at the bar. That becomes important unless I don’t want it to be, unless I want to cut them out and not show it to you. I think that helped ratchet up the tension as things went on.

Q: One of the limitations with 70mm film is that the magazines are very short, a little wonky but it means you have very short takes and yet you were able to have quicker cameras with a lot more film so you could shoot your actors for six and seven minutes at a time.

Tarantino: Yeah, even longer than that. Panavision came up with 2,000-foot mags where we were able to shoot for 11 minutes at a time. I can’t even imagine doing this material if we had to break it up into four-minute takes. . The Weinsteins were very generous with me so I didn’t have to dole out the footage in a certain way. I wasn’t completely cavalier about it, but I didn’t really change my shooting style for it. That wouldn’t have been a good idea to completely change my shooting style. So I shot the way I wanted to shoot.

The only real disadvantage I felt at the time, which I don’t feel now, was that we weren’t able to get a zoom lens. I’d really gotten used to using a zoom lens. But that was kind of a nice thing to be forced to not use all the tools that I’d gotten used to, and to be able to work in a different way.

Q: As a filmmaker you’re always more interested in the past, whether it’s historical periods or cinematic styles. Have you ever have a hankering or how you think you’d tackle it if you looked in the other direction, not necessarily making a film set in the future but adapting your style away from Westerns and the classic crime dramas that audiences know you for?

Tarantino: That’s a really interesting idea. I don’t think anyone has ever proposed it exactly the way you proposed it to me. Everyone always talks about the science-fiction genre, in particular, which always makes me think about people in spaceships. I can appreciate that but that’s not really where I think my dramatist aspect lies. The way you posed it, I don’t think I’ve ever thought about it as far as dealing with a future society like ours but what would that entail and what would it mean to jump 20 or 50 or 100 years in the future and literally look at it from that point of view. I never really thought about that before but that’s a profound thought, I have to admit.

Q: Does making a period film allow you the ability to comment on the present in ways that a present-day film doesn’t?

Tarantino: We can all point at versions in cinema history that has been profound. I do like putting scenario first. I do like putting story first and I actually like masking whatever I want to say in the guise of genre, so I could say it with my left hand and then deal with the right hand what the genre dictates. However, in this instance, it’s one of the benefits of the Western genre. I think there’s no other genre that deals with America better in a sub-textual way than the Western being made in the different decades. For example, the ‘50s Westerns very much put forth an Eisenhower idea of America and the American exceptionalism aspect of it, whereas the Westerns in the ‘70s were very cynical about America.

It was a drag that that first draft of the script got out when it did. However, when we were making this movie, it was during that last year-and-a-half when many of the themes that we were dealing with we were watching on television when we got home. We would come to the set and we would talk about them. The one good thing about the script getting out there is I’m on record for having written this before all the **** started popping off in the last year.

Q: Do you have any inkling of what the police unions have in store for you after that threat that they issued? Do you think that it’s those people who should be seeing the movie instead of boycotting it?

Tarantino: Yeah. I mean it’s funny because people ask me, “Are you worried?” The answer is, “No, I’m not worried because I do not feel that the police force is this sinister Black Hand (mafia) organization that goes out and ***** up individual citizens in a conspiracy kind of way. Having said that, civil servants shouldn’t be issuing threats, even rhetorically, to private citizens. The only thing I can imagine is that they might be planning to picket one of the screenings or something, maybe picket the premiere, maybe picket one of the 70mm screenings, or something like that.

So no, I don’t have any inkling, and I haven’t heard a whole lot about it other than (NYPD Union President) Patrick Lynch is keeping the fire on simmer.

I do think it’s unfortunate that because I do respect the good work that the police do. I live in the Hollywood Hills (Calif.). When I see a cop driving around there, I actually assume that he has my best interest at heart and he has the best interest of my property at heart. I think if you go to Pasadena, they would say the same thing. I think you’d knock on doors in Glendale and ask them they’d say the same thing. If you go down to Century Boulevard and start knocking on apartment doors in Inglewood they’re not going to say the same thing. I think all that was put into place about 30 years ago when we declared a war on drugs and actually started militarizing the police force.

You’re not going to have the police force representing the black and brown community if they’ve been spending the last 30 years busting every son and daughter and father and mother for every piddling drug offense that they’ve ever done, thus creating a mistrust in the community. But at the same time you should be able to talk about abuses of power and you should be able to talk about police brutality and what in some cases are, as far as I’m concerned, outright murder and outright loss of justice without the police organization targeting you in the way that they have done me.

Q: In a sense, you created your own genre. Your movies are powerful and thought provoking and often dance on the edge of being politically correct. What are your thoughts on being politically correct in today’s society?

Tarantino: I don’t have much thought on that other than in a conversation like the way you’re having it right now. I just don’t think about it that way. One could be inclined to say, “F this political correctness.” I don’t have time for that. But in polite society there is such a thing as sensitivity to some issues as time has gone on.

There was a time that we weren’t politically correct at all and we all wince at moments when we look and we see that. I don’t really know what the answer is as far as that is concerned. However, me as an artist, I don’t really think about it at all. It actually is not my job to think about that, especially with me as a writer and as a filmmaker but I’m not worried about the filmmaking part because if I’d written it, that’s what I’m going to do. But, particularly as a writer, it is my job to ignore social critics or the response that social critics might have when it comes to the opinions of my characters, the way they talk or anything that can happen to them.

We can talk about the race stuff but I’m sure some people here sitting in the room might be uncomfortable about the violence that is handed out to Jennifer’s character. Actually, I’m playing with that in the course of the movie. When she gets that crack in the head by John Ruth (Russell’s character) at the beginning of the movie, it is meant to send a shockwave through the audience. You’re meant to think. You’re not necessarily meant to like Daisy Domergue (Leigh’s character) in that moment but you are meant to think that John Ruth is a brutal bastard at that moment because that does seem like a rather overreaction to what she did and what she said. Time goes on, and you see how you feel about the characters, but it’s meant to do that. There is this aspect of the way this story works, in general, which is I have trapped nine people—if you include O.B. (Jackson, James Parks’ character). He’s not part of The Hateful Eight because he’s not hateful. It’s the Hateful Eight and O.B.

But, the way the story works, it’s the tension that we’re talking about, the pressure cooker that we’re talking about. Because, if you know where I’m coming from in that vaguely Sam Peckinpah way, to some degree or another anything can happen to these characters. Any piece about racist violence could happen to them. I paint in a system where there aren’t color book lines. I can cross those lines the way graphic novels do. I don’t mean graphic novels as in a comic books, but the way novels that deal with violence kind of almost seem to go anywhere in a way that movies aren’t allowed to go.

So, in that scenario, I’m going to make it that with seven of these characters, anything can happen to them but when it comes to this eighth character I have to protect her because she’s a woman and she can’t have the destiny that can happen to any of these other characters. No, that goes against the entire story. I’m not going to think like that. When I think of basically an artistic hero in that predecessor when it comes to that I think of somebody like (the late controversial British filmmaker) Ken Russell who was raked over the coals by the press in England constantly for the boundaries he pushed. He was like, “Don’t let these people get you down because I don’t think about them.” I can’t think about them. It’s my job not to think about them because I believe in what I’m doing 100 percent and I am doing what I’m doing and if you don’t like it don’t go see it.